This report summarises some of the key findings from the part of the 2015 working conditions survey in mainland Portugal that was addressed to workers. The survey found high levels of exposure to physical risks, high work intensity, and challenges in balancing working time with private life, with a high proportion of workers claiming that their pay was not proportionate to their performance and efforts.

Overview of survey

The 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal was composed of two strands: one focusing on companies and the other on workers. This spotlight report focuses on the strand addressed to workers.

The survey (PDF) was conducted by the Centre for Studies for Social Intervention (CESIS) at the request of the Portuguese labour inspectorate, the Authority for Working Conditions (ACT). It covered the following topics:

- employment status;

- type of work contract;

- working time duration and organisation;

- balancing paid work with personal and family life;

- work organisation;

- physical and psychological risk factors;

- health, well-being and safety;

- workers’ information, consultation, participation and training (regarding health and safety);

- protection during pregnancy, breastfeeding and parenthood;

- substance use;

- earnings;

- job security.

The design of the questionnaire was based on Eurofound’s European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS). However, several new questions were added (for example, on parental leave) and the contents of part of the questionnaire (such as exposure to risks at the workplace) was adapted to the Portuguese legal framework. Furthermore, since the initiative of this survey was framed by the National Strategy for Safety and Health at Work, special emphasis was given to occupational health and safety.

Methodology

The survey covered a representative sample of 1,500 employees aged 18 or over in all sectors of economic activity in mainland Portugal.

The sample was stratified by the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS II) and by the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE) Rev. 2 main sections, according to the last data published by Statistics Portugal (INE) (17 June 2011) on all activities except Section O (public administration and defence; compulsory social security). Since the information on this section does not exist in INE, it was obtained from the General-Directorate of Public Administration and Employment, Department of Statistics on Public Employment, Boletim Estatístico do Emprego Público, BOEP No. 13, October 2015.

The respondents were selected by the random route sampling method. This randomised sample allowed for a balanced distribution in terms of age group and gender; 743 women and 757 men were surveyed.

The fieldwork took place between 10 October and 4 December 2015.

Data were collected through a paper-based questionnaire administered face-to-face at each worker’s home.

Several quality control procedures were implemented for the fieldwork and in the completion of the survey database. These included:

- permanent monitoring of the interview, to ensure the proportionality of the strata;

- all the interviews being revised answer by answer (in cases of non-conformity, omissions or incoherencies, the interview was repeated);

- a second quality check on a random sample of 20% of the interviews conducted by each interviewer via phone contact with the interviewee.

Job quality

This short report aims to shed light on the findings of the survey related to job quality, adopting a gender-sensitive analysis. The terminology used by Eurofound for the development of the job quality indices in the Sixth European Working Conditions Survey – Overview report (2016) is used as much as possible and adapted to the existing national survey data.

Main findings

Physical environment

The most prevalent physical risks identified by the survey were related to repetitive hand or arm movements, and standing for long periods of time – 83.2% and 72.1% of the workers reported being exposed to these risks, respectively, at work (at least one-quarter of the time) (see Table 1).

Working environments are also characterised by exposure to several other physical risks. Those affecting a large part of workers were:

- tiring or painful positions (46.8%);

- working with computers or display screen equipment (46.1%);

- sitting for long periods of time (42.5%);

- carrying or moving heavy loads (29.5%).

In general terms, male respondents tended to be more exposed to physical risks at work than women. However, there are specific physical risks that affect mostly female respondents, such as:

- working with computers or display screen equipment;

- sitting for long periods of time;

- lifting or moving people.

Table 1: Exposure to physical risks (at least one-quarter of the time) (%)

| Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

Tiring or painful positions | 46.8 | 53.1 | 40.4 |

Lifting or moving people | 5.4 | 4.8 | 6.1 |

Carrying or moving heavy loads | 29.5 | 38.6 | 20.2 |

Repetitive hand or arm movements | 83.2 | 84.7 | 81.7 |

Standing for long periods of time | 72.1 | 77.8 | 66.4 |

Sitting for long periods of time | 42.5 | 36.9 | 48.2 |

Working with computers or display screen equipment | 46.1 | 38.3 | 54.0 |

Being subject to vibrations caused by instruments/machines | 15.5 | 25.6 | 5.1 |

Being subject to loud noises | 18.5 | 27.6 | 9.2 |

Performing tasks with insufficient lighting | 11.6 | 14.9 | 8.3 |

Use of hazardous machinery and work equipment | 19.1 | 30.5 | 7.5 |

Carrying out works at height | 9.2 | 17.2 | 1.1 |

Digging ditches | 2.8 | 5.7 | 0.0 |

On-board activities (in vessels) | 1.7 | 3.0 | 0.1 |

High temperatures | 15.3 | 22.5 | 7.8 |

Low temperatures | 12.0 | 18.0 | 5.5 |

Smoke inhalation | 7.8 | 14.0 | 1.5 |

Gas inhalation | 6.9 | 12.4 | 1.4 |

Handling or contact with mixtures or hazardous chemicals | 4.2 | 5.9 | 2.5 |

Working in explosive atmospheres | 1.8 | 3.3 | 0.2 |

Handling or contact with contaminated products or materials | 4.7 | 4.1 | 5.3 |

Working with non-ionising radiation | 1.8 | 3.2 | 0.5 |

Working with ionising radiation | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 |

Working with medium and high voltage electrical currents | 4.2 | 7.3 | 0.8 |

Being subject to high pressure (hyperbaric work) | 2.7 | 1.9 | 0.1 |

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

Working environments in the construction sector, followed by those in manufacturing, accommodation and food service, were found to have a higher exposure to the most common physical risks than other sectors.

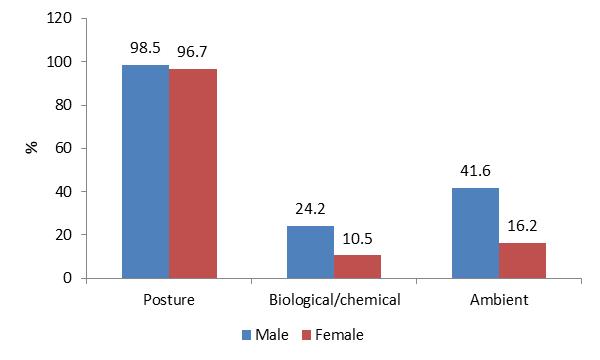

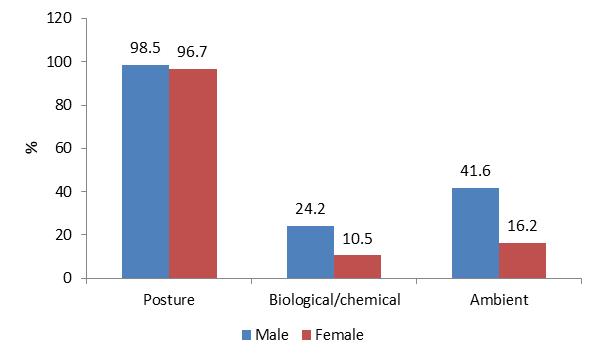

Based on questions in the survey on exposure to physical risks, three combined categories were determined:

- exposure to posture-related risks;

- biological and chemical risks;

- ambient risks.

The survey found that posture-related (ergonomic) risks were the most prevalent and affected men and women in a similar way (see Figure 1). Men reported a higher exposure to the other two categories, while ambient risks showed a larger gender disparity (25.4 percentage points).

Figure 1: Exposure to posture-related, ambient and biological and chemical risks, by sex (%)

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

Work intensity

Work intensity reflects the level of work demands in the job: meeting quantitative demands and experiencing emotional demands. Work demands are often associated with work stress.

Quantitative demands

- working at high speed;

- working to tight deadlines;

- the ability to take a break;

- not having enough time to do the job.

- around 68% report working at high speed (at least one-quarter of the time);

- about 60% report working to tight deadlines (at least one-quarter of the time);

- 21% report they can rarely or never take a break when they wish;

- 3.8% report that they rarely or never had enough time to do their job.

Figure 2: Quantitative demands, by gender (%)

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

Sectors such as manufacturing, construction, and accommodation and food service activities were the ones where working at high speed was most common. The need to work to tight deadlines was most often found in professional, scientific and technical activities, and manufacturing.

Work intensity varied according to the qualifications of workers:

- middle managers and highly qualified professionals reported lower intensive work related to working at high speed;

- highly qualified professionals and, in particular, senior officials and managers reported higher time pressure related to working to tight deadlines.

Emotional demands

Emotional demands were more frequent in jobs that involved dealing with people such as co-workers, clients, passengers, students or patients), or handling angry and/or difficult clients.

Some 43.8% of workers reported being in direct contact with other people; 28.1% of the workers reported having to handle angry and/or difficult clients, customers or pupils (always or most of the time). These emotional demands are particularly experienced by women (see Table 2).

Table 2: Emotional demands, by sex (%)

| Total | Male | Female |

Dealing directly with people who are not employees at the workplace, such as clients, passengers, pupils, patients etc. (always or most of the time) | 43.8 | 35.2 | 52.3 |

Handling angry or difficult clients, customers, pupils etc. (always or most of the time) | 28.1 | 21.2 | 34.8 |

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

- wholesale and retail trade;

- repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles;

- accommodation and food service activities;

- education;

- human health and social work activities.

Work-related stress

Self-reported experience of work stress was found to vary with work intensity.

Some 31.9% of the workers surveyed said they experienced stress at work (‘always’ or ‘most of the time’), while 15.4% of the women and 12.3% of the men said they never did so.

The scope to take a break was found to be the type of quantitative demand contributing the most to increasing work stress. For example, the 47.5% of the workers who reported ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ being able to take a break when they wished also claimed work-related stress (‘always’ or ‘most of the time’).

Dealing with angry clients and not having enough time to do the job was also found to be related to work stress, with 34.2% and 35% of workers, respectively, experiencing these forms of work demands.

Working time

Working time quality includes working hours and working time arrangements. These clearly affect a person’s work–life balance.

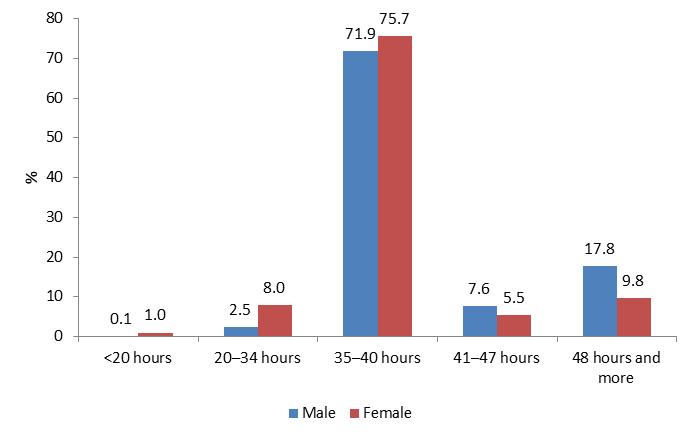

Working hours

More than 7 out of 10 workers usually worked between 35 and 40 hours per week in their main job (71.9% of men and 75.7% of women) (Figure 3). Almost 6% worked less than 35 hours per week, and about one-fifth worked more than 41 hours per week (and thus above the legal limit). Indeed, 17.8% of men and 9.8% of women reported extremely long weekly working hours of 48 hours or more. Gender differences are evident; it is mostly women (9.0% compared with 2.6% of men) who have shorter working hours, while men have longer working hours (25.4% compared with 15.3% of women).

Figure 3: Usual weekly working hours, by gender (%)

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

Part-time work (34 hours or less per week) was more frequent among female respondents aged either under 25 or above 55.

Long working hours (above 41 hours per week) was more common among male respondents aged 25–34, and among workers with lower levels of educational attainment.

Working time arrangements

- Almost one-third (32.1%) worked on Saturdays (at least once a month).

- About 15% worked on Sundays (at least once a month).

- Nearly 8% engaged in night work (between 22:00 and 05:00).

- Over one-quarter (26.8%) worked shifts.

- Some 16% had long working days (at least once a month).

Table 3: Atypical working hours, by sex (%)

| Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

Shift work | 26.8 | 26.9 | 26.8 |

Night work | 7.7 | 9.8 | 5.7 |

Work on Saturdays (at least once a month) | 32.1 | 34.9 | 29.2 |

Work on Sundays (at least once a month) | 14.9 | 15.3 | 14.5 |

Long working days – more than 10 hours a day (at least once a month) | 16.0 | 19.7 | 12.2 |

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

Work and private life

- Some 19% of women and 18% of men reported that they did not have a good fit between working hours and their family, personal or social commitments outside work.

- About one in three workers (35.5% of men and 30.7% of women) reported taking time off from their personal or family life to meet work demands (at least once a month).

- Nearly one in four workers (40.7% of men and 38.1% of women) reported that arranging to take an hour or two off during working time to take care of personal or family matters was ‘difficult’ or even ‘impossible’.

- It was also mostly men (48.3% compared with 44.4% of women) who reported not having taken parental leave due to work-related reasons (this question was asked of those who had had children and/or had adopted children in the five years prior to the survey, and declared not having taken the initial parental leave when their youngest child was born or adopted).

Table 4: Balancing professional, personal and family life, by sex (%)

| Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

Working hours do not fit in with family, personal or social commitments outside work (do not fit at all and do not fit very well) | 18.4 | 18.0 | 18.9 |

Take time off from personal and/or family life to meet work demands (at least once a month) | 32.4 | 35.5 | 30.7 |

It is difficult or very difficult to take an hour or two off during working hours to take care of personal or family matters | 39.1 | 40.7 | 38.1 |

Did not take parental leave due to work-related reasons | 47.4 | 48.3 | 44.4 |

Source: 2015 Working Conditions Survey in Mainland Portugal

Workers were more likely to say that the balance of their professional, personal and family life was poor if they worked nights; working shifts and long working hours were also reported to affect work–life balance (Table 5).

Table 5: Working time arrangements and balancing professional, personal and family life (%)

| Part-time | Full-time | Long working days (>10 hours) | Night work | Shift work |

Working hours do not fit in with family, personal or social commitments outside work (do not fit at all and do not fit very well) | 9.9 | 16.4 | 24.9 | 42.2 | 25.4 |

Take time off from personal and/or family life to meet work demands (at least once a month) | 25.9 | 30 | 44.4 | 63.1 | 46.3 |

It is difficult or very difficult to take an hour or two off during working hours to take care of personal or family matters | 25.3 | 38.1 | 46.5 | 54.4 | 45 |

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

Social environment

The term ‘social environment’ relates to the extent to which workers experience supportive social relationships from colleagues, as well as adverse social behaviour, such as bullying and harassment, and discrimination.

Social climate at work

The social climate at work was generally positive, with 81% of workers stating they had very good friends in the workplace. Furthermore, 72.6% say they felt ‘at home’ in the organisation where they worked.

Adverse social behaviour

However, there were reports of adverse social behaviour in the workplace in the 12 months prior to the survey.

- Almost 5% of workers – more women than men – reported exposure to adverse social behaviour. Episodes of physical violence, moral harassment, sexual harassment and/or intimidation/persecution were reported by 6.1% of women and 3.4% of men.

- Work-related discrimination (on grounds of age, race/ethnicity/skin colour, nationality, sex, religion, disability/incapacity, sexual orientation, take-up of parental leave, breastfeeding/lactation and/or absences related to caring for children) was felt by 5.8% of women and 2.2% of men.

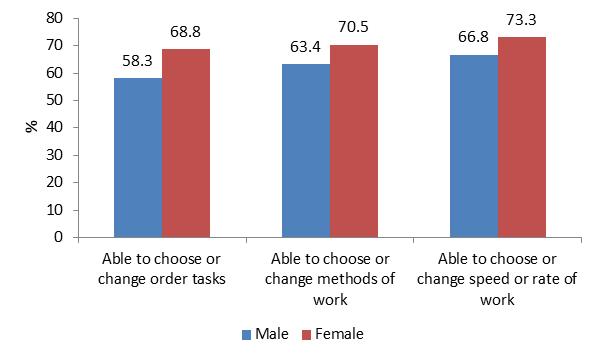

Discretion

Decision latitude

A significant proportion of the workers surveyed reported having scope for decision latitude, with women experiencing greater decision latitude than men (Figure 4).

- Some 63.5% had the ability to choose or change the order of tasks.

- Some 66.9% had the ability to choose or change their methods of work.

- Some 70% had the ability to choose or change the speed or rate of work.

Figure 4: Decision latitude, by sex (%)

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

The survey found that decision latitude increased with education; and female respondents were more educated – 24.1% of the women had a higher education degree, 10.1 percentage points more than the men.

Discretion also increased with qualification level, being greater among senior officials and managers, middle managers and highly qualified professionals.

Furthermore, greater scope for decision latitude was reported by workers who stated that their job offered good prospects for career advancement, as well as by those who perceived their organisation as motivating them to give their best job performance.

Organisational participation

About 44% of the workers (45% of women compared with 42.8% of men) reported being consulted before objectives were set for their work (‘always’ or ‘most of the time’). However, over 80% – again more women than men – stated that they were ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ involved in improving the work organisation or work processes of their department or organisation.

Prospects

A number of indicators are analysed under prospects: type of work contract; prospects for career advancement; job (in)security and employability; and earnings. A final reference to satisfaction with working conditions is also made.

Type of work contract

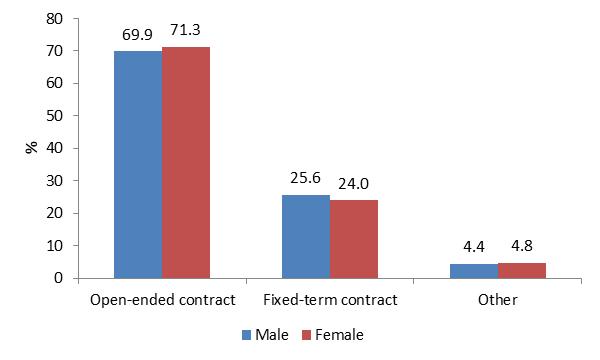

Although permanent open-ended contracts were the main form of employment contract reported by respondents (about 71% of the workers), about 27% had a different type of contract (mainly an open-ended one). A slightly higher percentage of women than men reported having an open-ended contract (71.3% and 69.9%, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Work contract, by gender (%)

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

Fixed-term contracts are more common among younger workers, with more than half of those workers aged up to 35, particularly women, having a fixed-term contract.

- information and communication;

- accommodation and food service;

- arts, entertainment and recreation;

- real estate;

- construction;

- education;

- transportation and storage services;

- agriculture, forestry and fishing.

Career prospects

About one in of four workers, either women (40.6%) or men (39.6%), stated that their job offered good career advancement prospects. Reporting good career prospects increased with education and qualification level.

In terms of sector, there were gender differences in the perception of good career advancement prospects. Women agreed (‘fully agree’ and ‘agree’) that their job offered them good career prospects especially when they worked in the following sectors:

- construction;

- information and communication;

- financial and insurance activities;

- professional, scientific and technical activities;

- arts, entertainment and recreation;

- public administration.

- Job security and employability.

In the case of men, the sectors mostly perceived as offering good career prospects were:

- electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply;

- water supply;

- sewerage, waste management and remediation activities;

- financial and insurance activities;

- other service activities.

Job security and employability

About 17% of the workers felt there was a possibility of losing their job in the six months after the survey (job insecurity). This concern was greater among those aged up to 35 (21%) (Table 6).

When asked if it would be easy to find a job with a similar salary if they were to lose or quit their current job (indicating their perceived employability), 32.9% of the male respondents, compared with 28.4% of women, agreed with this statement.

While older workers reported much less job insecurity than younger workers, their perceived level of employability was far lower.

Table 6: Job security and employability (%)

| I might lose my job in the next six months | If I were to lose or quit my current job, it would be easy for me to find a job of a similar salary |

Men | 17.6 | 32.9 |

Women | 17.2 | 28.4 |

Age group |

|

|

Less than 35 years | 21.0 | 36.8 |

35–49 years | 16.0 | 28.6 |

50 years and over | 13.8 | 23.8 |

Source: 2015 Working conditions survey in mainland Portugal

Earnings

The level of earnings and the perception of fair pay are crucial elements of job quality.

Many of the workers surveyed did not think their pay was in proportion to the work they performed and the effort they expended. About 58% of women and 67% of men felt they were not paid appropriately.

Satisfaction with working conditions

The vast majority (90%) of workers, both women and men, declared they were either ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with their working conditions.

Commentary

The working conditions survey in mainland Portugal conducted in 2015, was the first national working conditions survey implemented in Portugal since 1999–2000. ACT’s initiative in commissioning this survey was therefore welcomed, particularly by the social partners, but also by the scientific community.

When drafting this report, a request for comments and reactions to the survey was made to trade union confederations and employer organisations, as well as to ACT’s representatives on the Advisory Board for the Promotion of Safety and Health at Work. However, this commentary includes only remarks concerning the dimensions of job quality analysed above.

Three topics in the domain of job quality deserve specific attention. The first relates to the reported high level of exposure to physical risks associated with repetitive hand or arm movements. This finding substantiates the need for increased investment in this area, for example, in terms of training on ergonomics. According to the General Workers’ Union (UGT), there is a need to organise a national campaign – involving all relevant stakeholders – on the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders.

The second topic is exposure to psychosocial risks, and to adverse social behaviours in the workplace in particular. Some surprise was expressed, namely by UGT, at the relatively low levels of self-reported bullying/harassment and violence in the workplace in the survey. However, this may be associated with a problem of underreporting, and subsequent underestimation of the incidence of these forms of abuse in the working environments, due to either a lack of awareness about what is adverse social behaviour and/or a cultural reluctance to admit being a victim of violence or harassment.

The high level of reported satisfaction with working conditions is the third topic that attracted considerable attention from the social partners, namely by the Confederation of Portuguese Industry (CIP), as well as by the media. This finding should, however, be considered in the light of the very high unemployment in Portugal at the end of 2015. In this context, the simple fact of having a job, regardless of the working conditions offered, may have been a reason for satisfaction.

In terms of follow-up deriving from the results, some initiatives were reported as ongoing or under consideration.

ACT held a public event in April 2017 where the main findings of the survey were presented and discussed. This preceded an ongoing communication plan aiming at stimulating reflection on the main results of the survey throughout mainland Portugal.

The survey findings may also inform the monitoring of the National Strategy for Safety and Health at Work 2015–2020.

The implementation of new editions of the survey will depend on the definition of information needs at national level. In any case, particularly according to the views expressed by ACT, this instrument would benefit from being included in the national statistical system.