COVID-19 fallout takes a higher toll on women, economically and domestically

While women appear to be more resilient than men to COVID-19 in terms of health outcomes, that is not the case when it comes to the economic and social fallout. Measures taken by governments to control the spread of the virus are exacerbating gender divides in unemployment, domestic labour and financial security, all to the disadvantage of women. Meanwhile, work–life conflict is escalating as people work from home, with mothers of small children often bearing the brunt of the impact.

The imminent downturn in the wake of the lockdowns across Europe is likely to affect women’s job prospects more than men’s, and the first official labour market statistics seem to be a sign of things to come. Eurostat’s monthly unemployment data show that while the male unemployment rate increased from 6.2% in February to 6.3% in March 2020, the increase among women was greater, from 6.7% to 7.0%. [1] A similar trend is apparent in the United States, but more striking due to the availability of statistics for April. Here the male monthly unemployment rate increased from 3.3% in February to 4% in March and then jumped to 13% in April; unemployment among women hit 15.5% in April, rising from 3.1% in February and 4% in March. [2]

The reason why the COVID-19 measures are taking a disproportionate toll on women in the labour market is the gender imbalances across different jobs in the economy. Firstly, except for healthcare, men are more likely to work in what are considered essential economic activities, such as transportation, protection services (policing, for instance), farming, and maintenance and repairs, so they are more protected from unemployment. Secondly, the COVID-19 crisis has hit many services that involve frequent contact with customers and clients, and for which telework is not possible, such as retail, leisure and personal service activities, hospitality, and travel and tourism – some of the sectors in which women tend to dominate numerically.

Pandemic measures fuel work–life conflicts

In April 2020, Eurofound conducted a survey across the EU to find out how Europeans were coping with life during the pandemic. This confirmed that a lot of workers who were working from home had never done so before. It also showed that while before the crisis more women (64%) than men (57%) had never teleworked, women had now started to do so to a greater extent: 39% of women compared to 35% of men. And if we take a more granular look, we see that the figure rises to almost half of women with young children (46%).

Pre-pandemic, an increase of women teleworking would have been seen as a positive development, evidence that working time was becoming more flexible and work–life balance improving. But teleworking in a time of social distancing and lockdown is proving to be burdensome for many working mothers as they juggle work, home-schooling and care, all in the same pocket of space and time. Even before the crisis and despite more equal sharing of parenting and housework between the sexes in recent decades, care has continued to be mostly women’s work. The 2016 European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS) found, for example, that women spent 39 hours a week on average taking care of their children, against 21 hours spent by men. Women devoted an average of 17 hours a week to cooking and housework, compared with 10 hours for men. Today, as a result of lockdowns, women’s share of unpaid work is likely to have increased considerably, with children out of school and any older dependents in the home needing more care.

Concentration of activity in the home also means that conflicts between work and home life are sure to be on the rise. Our data confirms it, showing a general deterioration of work–life balance among workers in Europe. In April 2020, around 10% of Europeans found it difficult to concentrate on their work due to their family responsibilities; the percentage rises to 13% of men and 14% of women among those who are teleworking. These figures are much higher than recorded in previous surveys; for example, the 2015 European Working Conditions Survey recorded only 4% of respondents having this problem. [3] The same survey found that 13% of people felt that their jobs prevented them from giving the time they wanted to family, while 15% said they worried about work when they were not at work. In April 2020, many more people were in this situation: 19% felt their work was interfering with family life, while 30% were worrying about work outside of it.

Women with small children struggle most

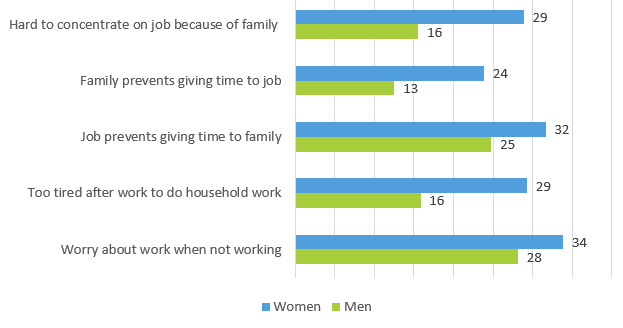

Among parents of young children (up to and including 11 years old), our data confirm that work–life conflicts are troubling women more than men, as illustrated in Figure 1. For instance, almost one-third of these women found it hard to concentrate on their work, as against one-sixth of men, while family responsibilities have prevented more women (24%) than men (13%) from giving the time they wanted to work. But work is also impinging on family life: 32% of women in this group say that their job prevents them from giving time to their family, against 25% of men.

Figure 1: Percentage of women and men with young children experiencing work–life conflicts

Note: The chart shows the percentage of women and men with children aged 0–11 years who responded ‘always’ or ‘most of the time’ when asked about each point.

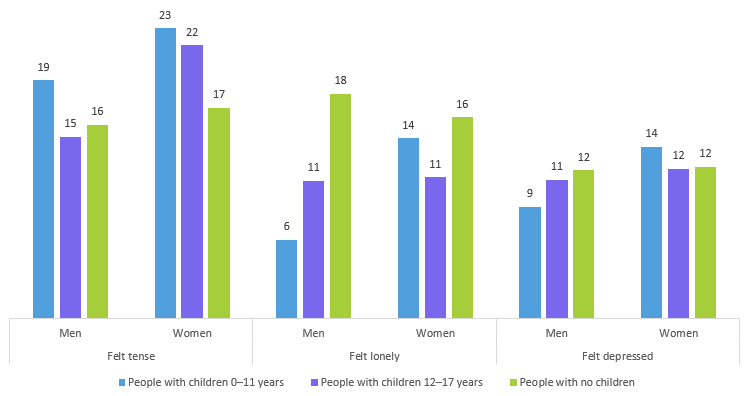

The strain caused by these conflicts may be affecting the mental well-being of women more than men, especially those with young children, although more research is needed to confirm this. According to our data, in April 2020, women with children aged 11 years old or younger were more likely to feel tense than men with children in the same age range (23% vs 19%), to feel lonely (14% vs 6%) and depressed (14% vs 9%). The same pattern occurs for women and men with children aged 12–17 years, although the differences are narrower.

Figure 2: Percentage of women and men feeling tension, loneliness and depression

Women feeling the financial strain more

The financial impact of the crisis has been similar for both sexes, with 38% of women and men saying their financial situation has worsened and that they expect it to deteriorate further. However, because women are more likely not to be in paid work or to be in low-paid and temporary jobs, they are more financially vulnerable than men.

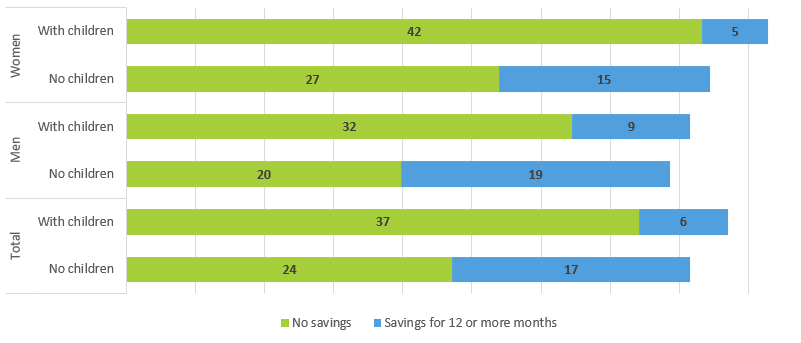

More women (24%) than men (22%) across Europe reported to our survey that they had difficulty making ends meet. This was particularly evident among women with children, where 32% are struggling to make ends meet, compared to 29% of men with children. Men are also more able than women to maintain their standard of living: 23% of men have no savings at all, compared to 31% of women, while 16% of men compared to 12% of women have enough savings to cover them for more than 12 months.

Figure 3 highlights the contrast between women and men with and without children in terms of the percentages who are highly insecure financially (no savings) and those who are comfortable (enough savings for more than 12 months). It shows that among those with children, a higher percentage of women have no savings and a lower percentage are comfortable compared to their male counterparts; the same pattern is evident among women and men without children.

Figure 3: Financial security of women and men with and without children compared (%)

The high level of financial uncertainty is undoubtedly part of the reason for the survey finding of reduced optimism among Europeans. Among men, 48% are optimistic about their own future and 34% are optimistic about their children's or grandchildren's future. For women, the equivalent percentages are 43% and 33%, respectively. Optimism was substantially higher in the 2016 EQLS, and the gender gap in optimism about one’s future was less, with 65% of men reporting optimism about their future, compared to 62% of women. But no gender difference existed regarding optimism about children’s or grandchildren’s future at that time, with 57% of both sexes reporting optimism for future generations.

While some of the gender unequal impacts of the current crisis might be temporary and could reverse once we have fully emerged from lockdown, others could have long-lasting consequences. It is essential, therefore, that the economic and social inclusion of women is at the centre of recovery measures. The European Commission has prioritised the eradication of pervasive gender inequality in society, recently publishing its Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025. This commitment should aid in focusing policymakers on the different pandemic experiences of women and men, to ensure that support is targeted effectively at those most in need. This is not just to defend the gains of recent decades in terms of gender equality or to rectify long-standing inequalities but also to build a fairer and more resilient world for the benefit of both men and women.

Image © David Pereiras/Shutterstock

References

^ Eurostat (2020), Euro area unemployment at 7.4% , news release, Brussels, 30 April.

^ United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020), Employment situation , PDF version, Washington, D.C., April.

^ Eurofound (2018), Striking a balance: Reconciling work and life in the EU , Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Authors

Massimiliano Mascherini

Head of UnitMassimiliano Mascherini is Head of the Social Policies unit at Eurofound since October 2019. He joined Eurofound in 2009 as a research manager, designing and coordinating projects on youth employment, NEETs and their social inclusion, as well as on the labour market participation of women. In 2017, he became a senior research manager in the Social Policies unit where he spearheaded new research on monitoring convergence in the EU. In addition, he led the conceptualisation of the 2026 European Quality of Life Survey. In 2025, he was awarded the Brendan Walsh prize for the best paper published in Economic and Social Review. Previously, he was scientific officer at the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. He studied at the University of Florence, where he majored in actuarial and statistical sciences and attained a PhD in Applied Statistics. He has been visiting fellow at the University of Sydney and at Aalborg University and visiting professor at the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

Martina Bisello

Martina Bisello is an Expert on Sustainability Transitions and Justice at the European Environment Agency.

Related content

14 December 2018

Striking a balance: Reconciling work and life in the EU

How to combine work with life is a fundamental issue for many people, an issue that policymakers, social partners, businesses and individuals are seeking to resolve. Simultaneously, new challenges and solutions are transforming the interface between work and life: an ageing population, technological change, higher employment rates and fewer weekly working hours. This report aims to examine the reciprocal relationship between work and life for people in the EU, the circumstances in which they struggle to reconcile the two domains, and what is most important for ;them in terms of their work-life balance. The report draws on a range of data sources, in particular the European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS) and the European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS).

23 January 2018

European Quality of Life Survey 2016

Nearly 37,000 people in 33 European countries (28 EU Member States and 5 candidate countries) were interviewed in the last quarter of 2016 for the fourth wave of the European Quality of Life Survey. This overview report presents the findings for the EU Member States. It uses information from previous survey rounds, as well as other research, to look at trends in quality of life against a background of the changing social and economic profile of European societies. Ten years after the global economic crisis, it examines well-being and quality of life broadly, to include quality of society and public services. The findings indicate that differences between countries on many aspects are still prevalent – but with more nuanced narratives. Each Member State exhibits certain strengths in particular aspects of well-being, but multiple disadvantages are still more pronounced in some societies than in others; and in all countries significant social inequalities persist.

17 November 2016