The pandemic aggravated labour shortages in some sectors; the problem is now emerging in others

Following the declines in employment rates and working hours across Europe in 2020, economies began to show signs of recovery during the first quarter of 2021. The gradual rekindling of economic activity has led to a surge in demand for workers and reawakened concerns over labour shortages. Difficulty filling vacancies was thought to be among the key factors holding back growth, competitiveness and service delivery in a number of sectors prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. Despite a temporary weakening in demand for labour during the pandemic, this was not the case in all sectors, with some seeing pre-existing shortages worsen.

Following the declines in employment rates and working hours across Europe in 2020, [1] economies began to show signs of recovery during the first quarter of 2021. The gradual rekindling of economic activity has led to a surge in demand for workers and reawakened concerns over labour shortages. Difficulty filling vacancies was thought to be among the key factors holding back growth, competitiveness and service delivery in a number of sectors prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. Despite a temporary weakening in demand for labour during the pandemic, this was not the case in all sectors, with some seeing pre-existing shortages worsen.

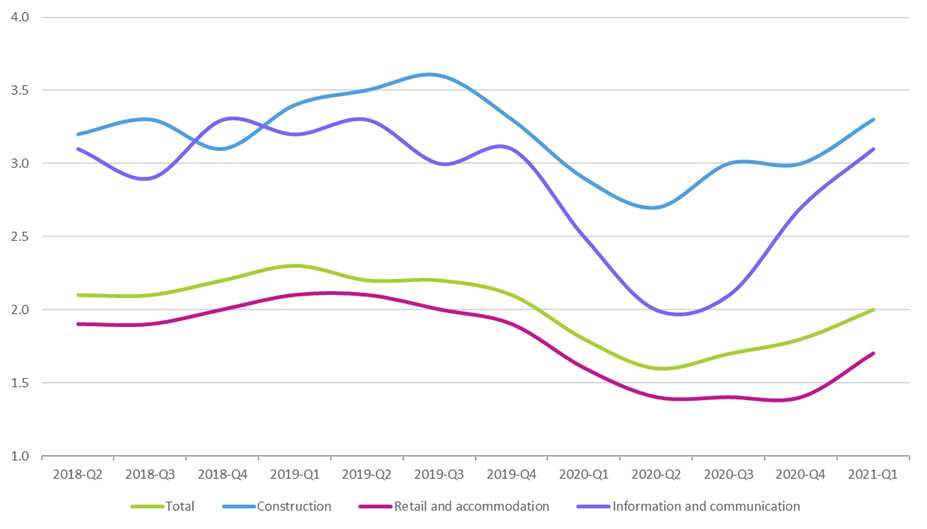

As Figure 1 shows, demand for labour, as measured by the job vacancy rate, reached pre-pandemic levels during the first quarter of 2021. Job vacancy rates are escalating in the construction and information and communication sectors, where skills shortages had become a structural problem, unrelated to short-term economic swings, well before the COVID-19 pandemic. In eastern Europe, the faster-than-predicted economic recovery, combined with growth in industrial output, has overheated the labour market and generated recruitment bottlenecks in the manufacturing sector. [2] Demand for workers has also surged in the hospitality sector, where the easing of the pandemic restrictions has seen employers struggling to find workers to fill vacancies.

Figure: Job vacancy rates in the EU27 (%), by sector, Q2 2018–Q1 2021

Many factors driving labour shortages

On the supply side, the current labour shortages are driven by the disruption of intra-EU mobility and migration flows, by workers switching sectors during the pandemic, and by workers’ reluctance to take up jobs in certain sectors because of concerns over wages and working conditions.

As regards mobility and migration, the COVID-19 pandemic has complicated procedures to apply for and obtain work permits, [3] increasing labour shortages in sectors such as agriculture and healthcare, where migrants make up a large part of the labour force. In Germany, inward migration fell by around 25% in 2020, leading to labour shortages across multiple sectors. [4] With restrictions on the movement of people across Europe’s borders dragging on in response to the emergence of new virus variants, it remains unclear when cross-border mobility will reach pre-pandemic levels.

Some workers opted to change jobs during the pandemic so that they could continue to earn a living. Reports from the hospitality industry show that uncertainty about business closures and reopening has led some workers to permanently change jobs. [5] In Ireland, the available information suggests that as much as 30% of the workforce in the hospitality sector has moved to another sector. [6] In Czechia, trade unions note that the pandemic has pushed women and young people out of the labour market while also diverting workers away from the hospitality sector towards employment offered by online platforms and delivery services. [7]

Low wages and poor working conditions are another reason for labour shortages in certain sectors. What is driving down employment in low-paid or low-skilled jobs is not the ‘fiscal profligacy’ of governments. Short-term working schemes and similar supports have provided a lifeline for both workers and employers while also ensuring that unemployment levels are kept in check. Rather than substantially discouraging workers’ return to work, these schemes have helped to avert a potentially disastrous shock to the labour market that could have seen many more workers sliding into unemployment and inactivity. What keeps workers from seeking employment in certain jobs is the lack of employment and income security, poor career prospects and the demanding nature of the work, combined with low pay and poor working conditions. In Greece, a country where labour shortages were almost non-existent prior to the pandemic, employers in the hospitality sector currently have difficulties finding workers, in part because of the unattractive job prospects. [8]

Pandemic aggravates shortages in health and care services

In 2020, all European countries reported an insufficient supply of nurses, general practitioners and long-term care workers. Labour shortages have long been a fact of life in healthcare. Data published by the World Health Organization show that the deficit of labour in healthcare is structural in the EU. Already in 2013, there was an estimated deficit of 1.6 million workers in the sector, which was predicted to rise to 4.1 million by 2030. [9] In countries like Austria, Germany and the Netherlands, provision of home-based long-term care relies heavily on workers from eastern Europe and other countries and therefore was badly impacted by travel restrictions. The long-term care sector already suffers from labour shortages due to its lack of appeal to workers, with relatively low levels of pay, challenging working conditions and often poor career prospects.

Addressing problem requires a complex policy mix

The pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities of European labour markets and the need for sustained investments in a suitable policy mix to address labour shortages. While investment in skills is vital for inclusive and sustainable growth in the context of the green and digital transitions, [10] the examples given above suggest that policies should also address the broader issues of job quality, migration and the enhanced integration of groups currently outside the labour market.

Publication: Tackling labour shortages in EU Member States

Image © Heidi/Adobe Stock Photos

References

^ DW (2021), Labor shortages are back to haunt Czech economy, 23 June.

^ Today (2021), Analysis: Remember me? With fast recovery, labour shortage haunts Eastern Europe, 8 June.

^ European Migration Network (2020), COVID-19’s impact on migrant communities, 24 June.

^ The Local (2021), Germany ‘desperately searching’ for skilled workers to plug shortage, 23 June.

^ RTÉ (2021), Some employers struggling to re-hire staff after lockdown, 18 May.

^ Irish Examiner (2021), Restaurants warn severe jobs crisis looming, 2 May.

^ DW (2021), Labor shortages are back to haunt Czech economy , 23 June.

^ Financial Times (2021), Greece struggles to find tourism workers due to risk of more lockdowns, 22 June.

^ Michel, J. P. and Ecarnot, F. (2020), ‘The shortage of skilled workers in Europe: Its impact on geriatric medicine’, European Geriatric Medicine, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 345–347.

^ European Commission (2020), European Skills Agenda , July 2020.

Authors

Dragoș Adăscăliței

Research officerDragoș Adăscăliței is a research officer in the Employment unit at Eurofound. His current research focuses on topics related to the future of work, including the impact of artificial intelligence on jobs, the consequences of automation for employment and regulatory issues surrounding the platform economy. He is also a regular contributor to comparative projects monitoring structural changes in European labour markets. Prior to joining Eurofound, he was a lecturer in Employment Relations at the University of Sheffield, Management School. He holds an MA in Political Science from Central European University and a PhD in Sociology from the University of Mannheim.

Tina Weber

Senior research managerTina Weber is a senior research manager in Eurofound’s Working Life unit. Her work has focused on labour shortages, the impact of hybrid work and an ‘always on’ culture and the right to disconnect, working conditions and social protection measures for self-employed workers and the impact of the twin transitions on employment, working conditions and industrial relations. She is responsible for studies assessing the representativeness of European social partner organisations. She has also carried out research on European Works Councils and the evolution of industrial relations and social dialogue in the European Union. Prior to joining Eurofound in 2019, she worked for a private research institute primarily carrying out impact assessments and evaluations of EU labour law and labour market policies. Tina holds a PhD in Political Sciences from the University of Edinburgh which focussed on the role of national trade unions and employers’ organisations in the European social dialogue.

Related content

11 March 2021

Disclaimer - Please note that this report was updated with revised data (specifically for Bulgaria) on 23 March 2021.

This report sets out to assess the initial impact of the COVID-19 crisis on employment in Europe (up to Q2 2020), including its effects across sectors and on different categories of workers. It also looks at measures implemented by policymakers in a bid to limit the negative effects of the crisis. It first provides an overview of policy approaches adopted to mitigate the impact of the crisis on businesses, workers and citizens. The main focus is on the development, content and impact of short-time working schemes, income support measures for self-employed people, hardship funds and rent and mortgage deferrals. Finally, it explores the involvement of social partners in the development and implementation of such measures and the role of European funding in supporting these schemes.

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)