Fired through a screen: The validity of digital dismissals in the EU

Published: 12 June 2025

Employers increasingly use tools such as email, SMS and messaging apps like WhatsApp or Signal to communicate with employees. While these technologies offer both efficiency and convenience, their use in communicating sensitive information, particularly for notifying employees of dismissal, raises legal concerns. This article explores the legal framework on dismissals across the EU, with a special focus on the use of digital means for communicating employment dismissals. Drawing on examples from various Member States, it examines the legal validity of digital dismissals.

In June 2024, employees of Nova Casale Srl, an Italian company associated with the electrical retailer Euronics, received their dismissal notices via WhatsApp. The decision to communicate dismissals via WhatsApp made national headlines in Italy and sparked swift criticism from trade unions. The controversy sparked a broader debate and raised key questions: What kind of digital dismissals are legally valid? Is an email more legally binding than a WhatsApp message? In many EU Member States, specific formal requirements aim to protect employees from unjust dismissal and define employers’ obligations. Can digital dismissal notifications satisfy these legal requirements? As workplaces increasingly rely on digital communication, understanding the legal landscape on digital dismissals becomes essential.

EU-level protection against dismissal

Protection against unjustified dismissal is enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. However, the enforceability of this right is limited, as Article 51 (1) of the Charter stipulates that it applies to Member States only when they are implementing Union law. Beyond Article 30, dismissal protection is only marginally addressed in EU legislation. While certain directives set out procedural safeguards in specific contexts or prohibit dismissal on discriminatory grounds, such as the Collective Redundancies Directive and the Transfer of Undertakings Directive, there is no directive that applies to dismissals more generally. Therefore, EU law offers protection against unjust dismissals only in specific cases. As a result, the laws governing dismissals vary widely across Member States, leading to a lack of harmonisation in this area.

Formal requirements for dismissal in national legislation

The most common formal requirement for dismissals in the EU is the written form, which is mandated in all but two Member States. This requirement supports verifiability and ensures that all necessary information is included. This requirement also helps avoid misunderstandings and legal disputes by providing a clear and documented record, which explains its prevalence across Member States.

In the EU, only Austria and Malta lack a general written notice requirement for dismissals. Therefore, in the absence of such a requirement, digital dismissal notices are permitted in both Member States. However, in the other EU Member States wherever written form is mandated, the validity of digital dismissals becomes more complex. For digital dismissals to meet the written notice requirement, they must be recognised as adequate methods of delivering dismissal notices. Across Member States, various methods of communication have been deemed acceptable under national legislation and case law. This article will explore three such methods: physical letters of dismissal, email, WhatsApp or SMS.

It is important to note that specific formal requirements may apply to certain protected categories of workers or be stipulated in collective agreements or individual employment contracts.

Physical letters

The most widely accepted method of communicating dismissal notices across EU Member States is through a physical letter, which satisfies the written notice requirement wherever it is mandated. In many Member States, it is either common practice or a legal requirement to deliver the dismissal letter in person, directly to the employee. This guarantees that the employee receives the notice and allows for confirmation of receipt through a signature, which is often required or strongly recommended to prove receipt.

Some Member States also permit the letter to be sent via secure postal delivery services, such as registered mail. This method is recognised in countries like Belgium, Luxembourg, Spain and Sweden, although its acceptance may be subject to certain conditions. For instance, in Sweden, registered mail is only deemed acceptable when personal delivery of the notice to the employee would present unreasonable obstacles for the employer (Section 10 of the Swedish Employment Protection Act).

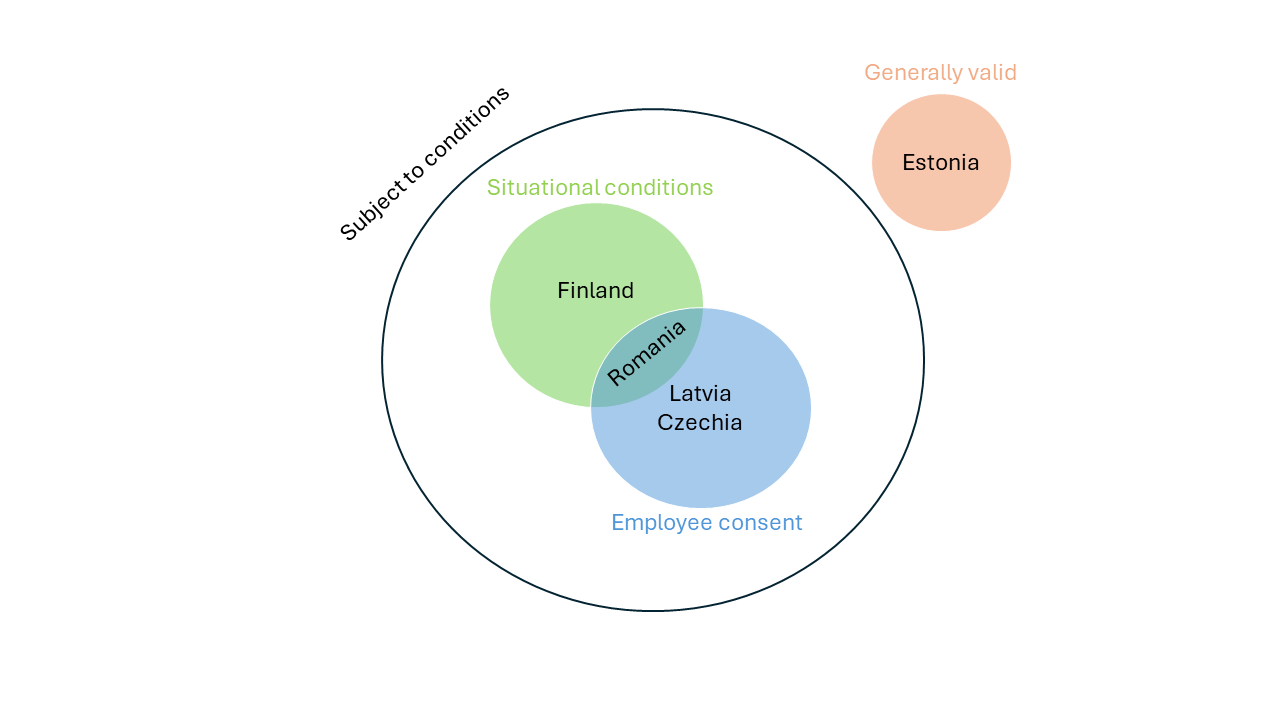

The use of email to communicate dismissal notices is accepted in a number of EU Member States, including Czechia, Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Romania. However, only Estonia considers email dismissals to be generally valid (Figure 1). In the other Member States, such dismissals are only valid if certain conditions are met.

In Estonia, email dismissals are considered valid as they fulfil the requirement for a written format that can be reproduced, which is the sole formal requirement outlined in Section 95(1) of the Estonian Employment Contracts Act. The approaches adopted in Czechia, Finland, Latvia and Romania are noteworthy, as they illustrate different approaches to balancing the convenience of email communication with the need to protect employee rights. In these Member States, the validity of email dismissal often depends on one or both of the following:

whether specific situational conditions are met (for instance, the employee is unavailable to receive an in-person delivery)

the employee’s direct or indirect consent to receive such notifications electronically

Figure 1: Validity of email dismissals in selected EU Member States

Source: Eurofound

In Finland, email dismissals are permitted only when in-person delivery is not feasible (situational condition), for example, if an employee is on annual leave (Section 4 of the Finnish Employment Contracts Act). Consequently, email may only be used in exceptional circumstances and should not be used as a standard method of dismissal.

In Romania, both situational and consent-based conditions need to be fulfilled. Email is only permitted if the employee has provided their email address to the employer (indirect consent), and email is already the standard method of communication between the parties (situational condition).

In Latvia, Section 101 of the Labour Law states that email dismissals using an electronic signature are valid if this method is explicitly agreed upon in the employment contract (direct consent).

In Czechia, Section 335 of the Czech Labour Code stipulates that email dismissals using an electronic signature are valid if the employee has given written consent and provided the employer with an email address for delivery (direct consent).

In contrast, several countries, such as Sweden and Germany, do not accept dismissals via email. Under Section 8 and 10 of the Swedish Employment Protection Act, dismissal notices must be provided in writing and delivered directly to the employee. If personal delivery cannot reasonably be required, the notice may be sent by registered mail to the employee’s last known address. In a decision by the Swedish Supreme Labour Court, the court found that while an email dismissal does not render the dismissal null and void, the employer must pay damages for failing to comply with the legal requirement of delivering the notice in the correct manner.

Similarly, in Germany, email dismissals are explicitly prohibited by law. Section 623 of the German Civil Code requires dismissal notices to be in written form and cannot be communicated in electronic format, such as email or other digital means.

SMS or WhatsApp

Other EU Member States, such as France and Italy, go even further and also allow dismissal notices to be sent via SMS or WhatsApp, provided certain conditions are met.

In France, Article L. 1232-6 of the French Labour Code requires, in principle, dismissal notifications to be sent by registered mail with acknowledgment of receipt. However, according to case law, a SMS or WhatsApp dismissal may be legally valid provided the employer has just cause and follows the proper dismissal procedure outlined by law.

This procedure includes inviting the employee to a preliminary meeting, explaining the reasons for the dismissal, and giving the employee an opportunity to respond before the notice is issued.

In Italy, Article 2 (1) of Law 604/1966 requires dismissals to be communicated in writing, but does not specify the method of delivery. However, case law has clarified that the chosen method of delivery must ensure that the employee both receives and acknowledges the notice for it to be valid. Additionally, it must be clear that the notice originates from the employer and clearly expresses the employer’s intent to dismiss the employee.

Consequently, an SMS or WhatsApp dismissal can be valid if it clearly expresses the employer's intent to dismiss, there is no doubt that the notice originates from the employer, and the employee is clearly aware of the dismissal. If assessed by a court, these requirements would likely be examined in cases such as the previously mentioned Nova Casale Srl dismissals via WhatsApp, to determine whether the conditions established in earlier rulings are met.

While France and Italy highlight two different approaches to integrating modern communication tools into dismissal processes, both emphasise that, for SMS or WhatsApp dismissals to be valid, the employer must express a clear intention to dismiss, and it must be ensured that the employee is made aware of the dismissal.

Conversely, Denmark has adopted a less restrictive approach. According to Section 2(7) of the Danish Salaried Employees Act, dismissal notices must be provided in writing. However, the law does not define the format of communication. As a result, dismissals through email, SMS or WhatsApp have been deemed as valid.

Conclusion

With the adoption of the Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030, the EU has set a clear goal to increase technology uptake among businesses. As a result, companies are likely to increasingly rely on digital tools for employee communication. Consequently, understanding the legal boundaries of what may and may not be communicated through digital means becomes increasingly important.

This article has provided an overview of how dismissal notices are treated across EU Member States when delivered via physical letter, email, SMS or WhatsApp. The findings reveal a diverse legal landscape: while some Member States adopt more flexible approaches to digital dismissals, others uphold the requirements for traditional written formats.

This article highlights the following main points:

Dismissal laws vary across Member States, meaning that both the validity of different types of digital dismissals and the criteria they must meet differ from one country to the next.

Physical letters of dismissal remain the most accepted method of communicating dismissal notices across the EU.

Digital dismissals are valid in some Member States, but their legal validity is often subject to specific requirements.

Image © ViacheslavYakobchuk/Adobe Stock

Note: This article is part of Eurofound’s activities under the European Restructuring Monitor (ERM), which maintains a legal database of national provisions on restructuring across EU Member States.

Eurofound recommends citing this publication in the following way.

Eurofound (2025), Fired through a screen: The validity of digital dismissals in the EU, article.

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)