Keeping careers alive as work transforms

In this article, Jean-Marie Jungblut looks at the health of careers in Europe. He argues that, since the average length of the most important job in a person’s life is over 20 years, time should be put aside in the middle of a career to check the fit between the worker and the job. Different scenarios can arise from such an exercise.

Careers are alive and well. Despite declarations that the gig economy and a generalised flexibilisation of working life will spell the end of careers, the data do not bear this out. While for many people the jobs they hold early in their career are short, a large majority will end up in a long-term employment relationship eventually. The average duration of the most important job in a person’s life is over 20 years, and over 90% of those who are close to retirement have been in their job for longer than that on average. Increasingly, workers work longer and retire later, and generally not because of economic necessity.

It is true that the industrial age with its large-scale companies that have quasi monopolies and offer lifetime careers to their workforces is a bygone model, if it ever really existed. Only half of new companies survive more than five years: think of start-ups, often created around an idea, or dot-coms or short-lived service enterprises. However, these companies represent only a small fraction of businesses and are usually small-scale enterprises typically employing fewer than five people. Most companies survive over time once they exist for a few years, and the larger they are, the higher their chances of survival.

Taking stock mid-career

The apparent contradiction between the high turnover of young companies and long-term employment relationships is therefore superficial. Nevertheless, it is crucial that workers and employers become more aware of labour market dynamics such as new skill demands related to the introduction of new technologies as well as labour and skill shortages due to demographic ageing. These developments will demand more, and more frequent, career changes by workers. Career change, however, does not necessarily mean changing one’s job. Rather it involves a joint commitment between employer and employee to invest in developing the employee’s career in a mutually beneficial direction. The mid-career review (MCR) has emerged as a setting for this type of career stock-taking.

An MCR is a systematic check of the fit between the worker and the job. It involves a structured process where employees review their career achievements critically, reflect on the years to come, focus on strength and weaknesses, and try to find an optimal fit between their expectations and the needs of their employer. It should examine a person’s circumstances in the round: finances, health, values, interests, skills, relationships and networking. The outcome should be open at the outset but in principle aim at achieving a mutually agreed development and action plan if necessary. This may lead to the worker acquiring new skills, changing tasks, changing work arrangements or transferring to other jobs as their working life evolves.

MCRs put into practice

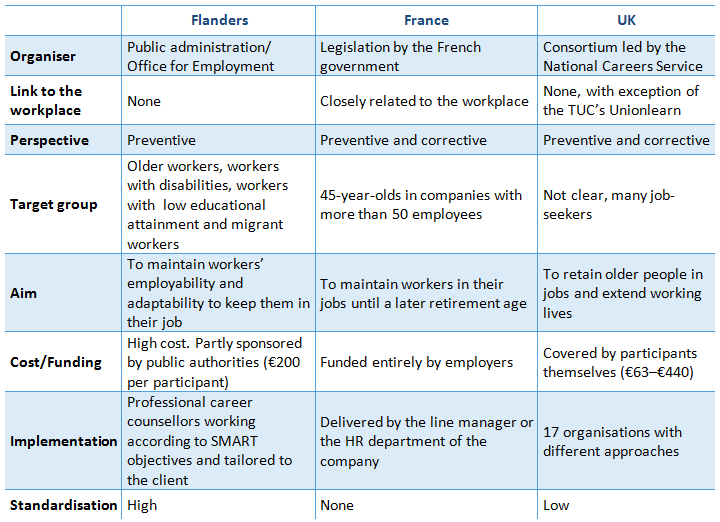

Are MCRs just another HR box-ticking exercise? We conducted case studies of three MCR programmes implemented in Flanders (Belgium), France and the UK, which showed they have some merit (see the table below for a summary). Among the participants in the Flanders scheme, almost two-thirds stayed with their current employer and said their job satisfaction had improved; one-third subsequently took part in training; and nearly half achieved the goals set during their trajectory-planning discussions within six months of finishing the scheme.

The UK programme enlisted 17 providers and attracted a lot of job-seekers – not the ideal target group. However, one of the providers was the TUC organisation Unionlearn, which engaged 45 workplace-based union learning representatives to deliver MCRs to 700 union members, well above the target of 400, most of whom were employees. Those involved rated the programme a success.

The French programme arose out of a change to the labour code that entitled all workers to request an MCR from their employers. Reviews were carried out by company HR departments or line managers. However, few employees took up the option; it seems that many saw it as a performance appraisal. Employees may also have been reluctant to share frankly with management their reservations or worries about their futures.

Each of the cases offers lessons from which to learn: the professional standards of the Flemish scheme, the involvement of external providers in the UK case, and the company-based approach in the French case, with the legal obligation to carry out an MCR if the employee requested it.

Summary of features of three different MCR programmes

Source: Eurofound (2016), Changing places: Mid-career review and internal mobility, p. 58

A model for MCR

The approach taken by Unionlearn seems promising as a model. The MCR is carried out by a trusted trade union intermediary in the workplace and takes place in three stages:

Establishing the framework, building trust with employers and educating workers about MCRs

One-to-one or group sessions where issues and themes are explored, aims set and actions planned

The interview and follow-up stage, where individual support is given and employers are engaged in the process

Just as it is risky for companies to stick to the same products and to fail to innovate, not being attentive to one’s career development, skills and life circumstances can lead to job loss. Particularly for workers aged 50+, losing a job can be catastrophic, as the likelihood of finding another is low. Career checks when employees are in their 40s, when it is still possible for people to change direction successfully, can help avoid the cliff edge of stagnation or job loss. For companies in the 21st century, their most precious resource is their pool of human capital. Those that do not take this on board fail to realise their full potential or, worse, go out of business.

Image: ©Shutterstock/Tommy Lee Walker

Author

Related content

17 January 2017

Demographic ageing poses the challenge of how to keep people in employment for longer without negatively affecting their health and well-being. The solutions are particularly critical for workers engaged in arduous work. This report examines how mid-career reviews can play a key role by clarifying workers’ options for remaining in work until a later retirement age. Following an exploration of career trajectories and transitions, the report focuses on arduous jobs: their incidence across Europe and the implications of such work for career and work sustainability. It examines various tools and strategies used by public authorities and social partners to keep workers in arduous jobs in employment longer. Finally, three case studies – from Belgium, France and the UK – of mid-career reviews undertaken either as pilot projects or as a legislative reform are presented.

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)

&w=3840&q=75)