Seniority entitlements: A policy of the past, or a fix for the future?

Seniority entitlements have largely been on the decline since the 1990s, and have been gradually phased-out from legislation in Europe, as well as in collective agreements. However, it would be premature to dismiss seniority-based entitlements as a thing of the past, as they remain in force across Europe, even if the more expansive term of ‘relevant experience’ is preferred. As we look to the future, we ask whether seniority-based entitlements have a renewed role in a European labour market challenged by demographic ageing and a need to keep people working for longer, or whether they are a relic of the past that contribute to inter-generational inequity, under-performance, and lower employment prospects of older workers.

Phased-out, but sticking around

Since the 1990s, seniority entitlements have been removed from many pieces of legislation or from collective agreements. They were rendered less ‘automatic’, were placed alongside other criteria or made conditional, and some have become privileges rather than entitlements.

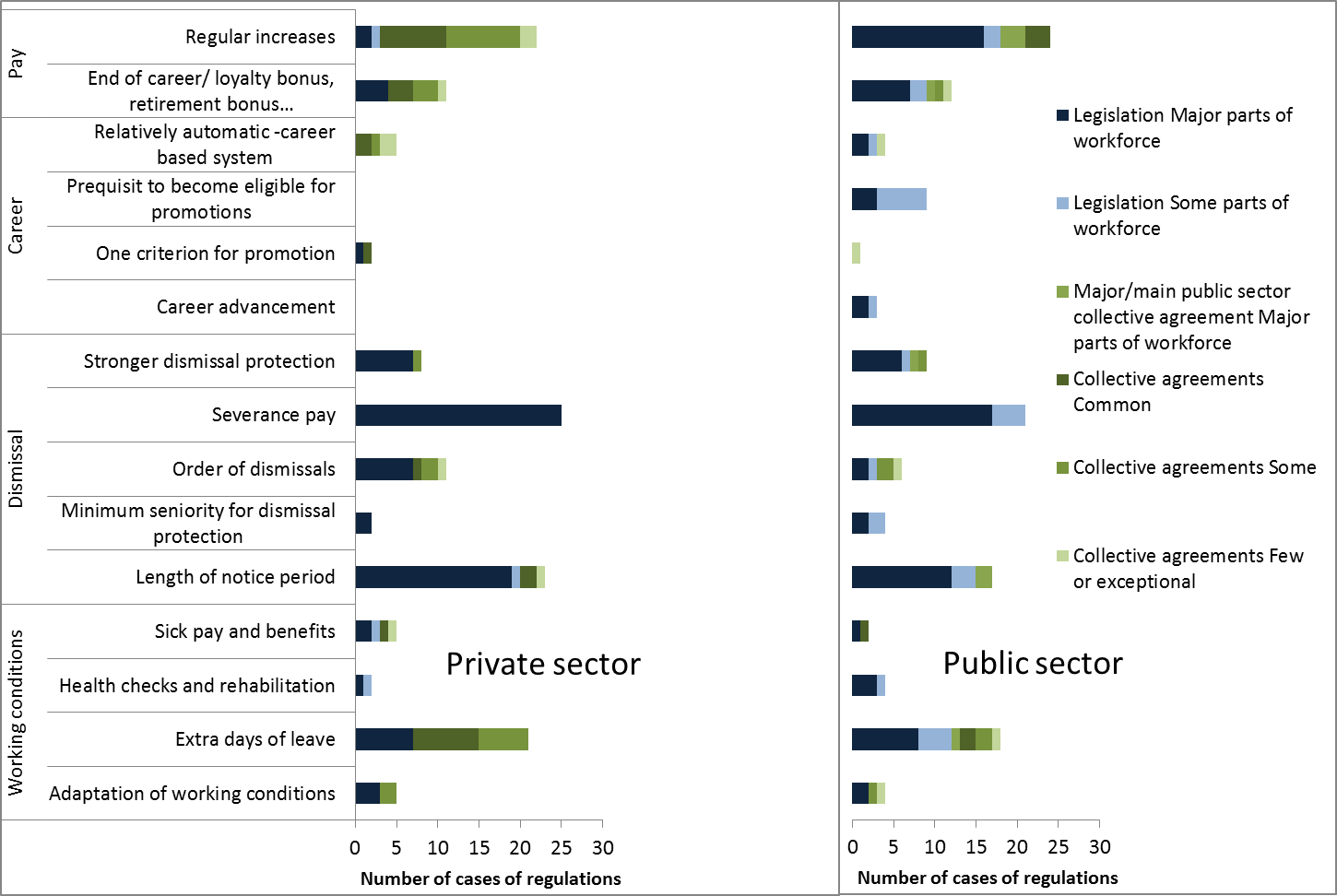

Yet, our new report shows that many such seniority aspects remain to be in place across Europe in legislation and within collective agreements. This is more often in the public than in the private sector, and in countries with sectoral bargaining. These entitlements most commonly relate to dismissal protection, including seniority-based notice periods and severance pay, and in some countries also determine the order of dismissals during collective redundancies. Seniority entitlements also relate to extra days of annual leave with length of service – which is laid down in legislation or collective agreements in half of the Member States.

Seniority-based entitlements in the private and public sectors of the EU28 and Norway.

Number of country cases, where such entitlements were found to exist and type and degree of regulation. Source: Eurofound (2019) based on Network of Eurofound correspondents.

Seniority pay is more frequently found in the public sector and then sometimes combined with different aspects of seniority-based career advancement, often of an ‘eligibility based’ type, where people are entitled to opt for promotion only after a certain number of years. Only three Member States – Belgium, Bulgaria and Slovenia – have legally based seniority allowances, which grow linearly with every year of service. In these Member States debates around reforming such entitlements have become ever more prominent recently. Seniority pay scales also continue to exist within private sector collective agreements in most Member States.

Turbulence over change

A lack of recognition of seniority has resulted in high-profile cases of discontent among workers over the past 12 months. The Ryanair dispute of summer 2018, where Irish pilots have demanded that their seniority be considered for determining aspects of working conditions, such as their allocation to bases, shows that in contexts where seniority has been removed completely, and in the absence of other transparent criteria, the perceived injustice can rise to levels which take employees to ‘the streets’, or in this case perhaps the runways. The dispute has been successfully resolved with the introduction of a transparent seniority list.

Reforming seniority-based pay can be difficult, as the recent protests of nursing staff in a Viennese hospital showed. As new staff was recruited under a pay agreement with flatter earnings curves and higher entry level pay, the incumbent staff, being excluded from the transition to this new agreement, demanded ‘equal pay for equal work’ and questioned why someone serving longer should earn less.

A career-long issue

In both academic literature and policy debates seniority has been predominantly discussed in connection with older workers: if seniority entitlements impact the likelihood of older workers getting laid off early and hindering their (re-)employment prospects, or whether stronger seniority-based dismissal protection affects productivity negatively.

Eurofound’s new report on Seniority-based entitlements shows that these entitlements affect people throughout their working lives – not only at the later stages of their careers. A considerable number of seniority entitlements are ‘eligibility based’, granting employees access to more favourable benefits or terms and conditions of work, once a certain minimum length of employment is reached. Those most likely to miss out on such entitlements are in more precarious positions, switching jobs frequently, without the individual bargaining power to secure their rewards for previous experience, or more likely to interrupt their careers due to family duties. The newer – and more inclusive –regulations therefore regard seniority as relevant experience within an industry, a similar role or even based on a set of pre-defined skills, which are likely to correlate strongly with the number of years of experience, rather than as length of employment with the same employer; or they specifically take certain leave periods, such as parental leave, into account.

Often the term ‘seniority’ has even vanished from such regulations and was relabelled to relevant ‘experience’ or ‘relevant qualifications for a certain position’. Examples for such a renewed definition in collective agreements can be found in several countries with a traditionally strong sectoral bargaining – Austria, Denmark, Germany, Norway or the Netherlands. Having such new types of collective regulations in place can therefore counteract the dualization or segregation of labour markets in which predominantly ‘insiders’ benefit.

The relevance of experience

While the future is hard to predict, we can surmise that seniority – even if not labelled as such – will be here to stay, as one important element of the negotiators and the human resources managers, and maybe also the legislators’, toolbox. Why? The new report goes into extensive detail, but in a nutshell, seniority can be used to retain staff, which gains importance in time of labour shortages and demographic change. They are also an impartial, transparent, easy to establish, and therefore cost-efficient criterion for ranking employees and rewarding them.

Recent disputes, such as those detailed above, have shown that seniority-length of service is perceived as fairer than other criteria and it will be much less costly to apply, particularly when individual performance is hard to measure. Yet, some of their main disadvantages – including the hinderance of worker mobility or making older workers more expensive and therefore harder to re-employ, or penalising workers with career interruptions - have to be overcome. Seniority may be here to stay in some form, but we need a fresh approach.

Authors

Christine Aumayr-Pintar

Senior research managerChristine Aumayr-Pintar is a senior research manager in the Working Life unit at Eurofound. She coordinates Eurofound’s research on social dialogue and industrial relations and oversees the Network of Eurofound Correspondents (NEC). Her primary research expertise – approached from a comparative EU-wide standpoint – centres on minimum wages, collectively negotiated pay and gender pay transparency. Prior to joining Eurofound in 2009 she was a labour markets and regional economics researcher at Joanneum Research in Austria. She earned a Master's degree in Economics and a PhD in Social Science/Economics having studied economics in Graz, Vienna and Jönköping.

Related content

17 April 2019

Seniority systems – schemes that allot improving employment rights or benefits to employees as their length of employment increases – have not been widely studied. This report provides the first comprehensive study comparing the design and spread of seniority-based entitlements (SBEs) in Europe and mapping related policy debates. It is primarily based on contributions from the Network of Eurofound Correspondents, covering the 28 EU Member States and Norway, but also presents aggregate seniority-earnings curves for the EU based on data from the Structure of Earnings Survey. The aim of the report is to take stock of the currently existing different types of SBEs in the private and public sectors. It concludes that despite an obvious trend to remove them from regulations or reform them, a substantial amount of such entitlements is here to stay. Paradoxically, countries which have regulations on seniority pay in place tend to have flatter aggregate seniority-earnings curves than countries without such regulations.

20 March 2019