What now for Europe?

The votes have been cast, tallied and declared and we can now see the political landscape of the new European Parliament. It is a complex picture: there has been growth of far-right and populist parties, but well short of what was projected, and at the same time there has been a boost for pro-European liberal and Green parties. To what extent have mixed developments in employment and quality of life contributed to this more fractured political landscape? And can the EU continue to deliver to the more diverse demands of citizens across Europe?

A Union in recovery

The European elections have come at a time when the EU is in good economic health. According to the majority of economic indicators, we have recovered from the most severe financial crisis in Europe since the war. However, over the past five years the Union has been challenged on all fronts, from the sustainability and stability of the euro, to the undermining of social resilience from the crisis, and capacity to deliver better living and working conditions to all.

Questions have also been raised about the ability of the eurozone to face new economic shocks, and the Union’s political capacity to coordinate a common response to humanitarian crises that have seen so many refugees arrive at our shores. Nationalist and populist parties have made political capital from these challenges, traditional parties have felt the squeeze from an anxious electorate and, infamously, a Member State has requested to leave the EU for the first time.

This modern-day reality is, in some respects, the political aftershock of an economic crisis that has been largely overcome. Since 2013, the EU has seen sustained growth, achieved record levels of employment, reduced social exclusion and increased institutional trust in most Member States. Social policies have again come to the fore of the EU Agenda, complementing the criticised overemphasis on monetary-centred policies, and the Union is once-more converging upwards in many living and working standards indicators.

Even if most indicators have been redressed, negative perceptions about EU policies linger, facts are distorted or ignored, and trust has been slow to rebuild. There needs to be more progress to ensure that the recovery is felt by all, and aggregate figures can disguise difficulties still felt by some countries and groups. Discontent initiated by social unrest is also now maintained by a post-economic narrative that focuses on security, protectionism, and identity.

Eurofound has chosen this pivotal moment of transition to publish its new edition of Living and Working in Europe, summarising relevant evidence of work and life in Europe between 2015 and 2018; findings that help to make sense of recent economic, social and working life developments, and guide policy action in the immediate future.

Growth and jobs first

The data presented in Living and working in Europe shows that ensuring financial stability and economic growth was a logical first focus of the Commission during the crisis in order to put the EU back on track. The Investments Plan for Europe, or so called “Juncker Plan”, was put front and centre of the Commission’s overall priorities. €315 billion in additional investment was mobilised, and the overall strategy was supported by the European Parliament, which extended its duration and capacity to €500 billion by the end of 2020.

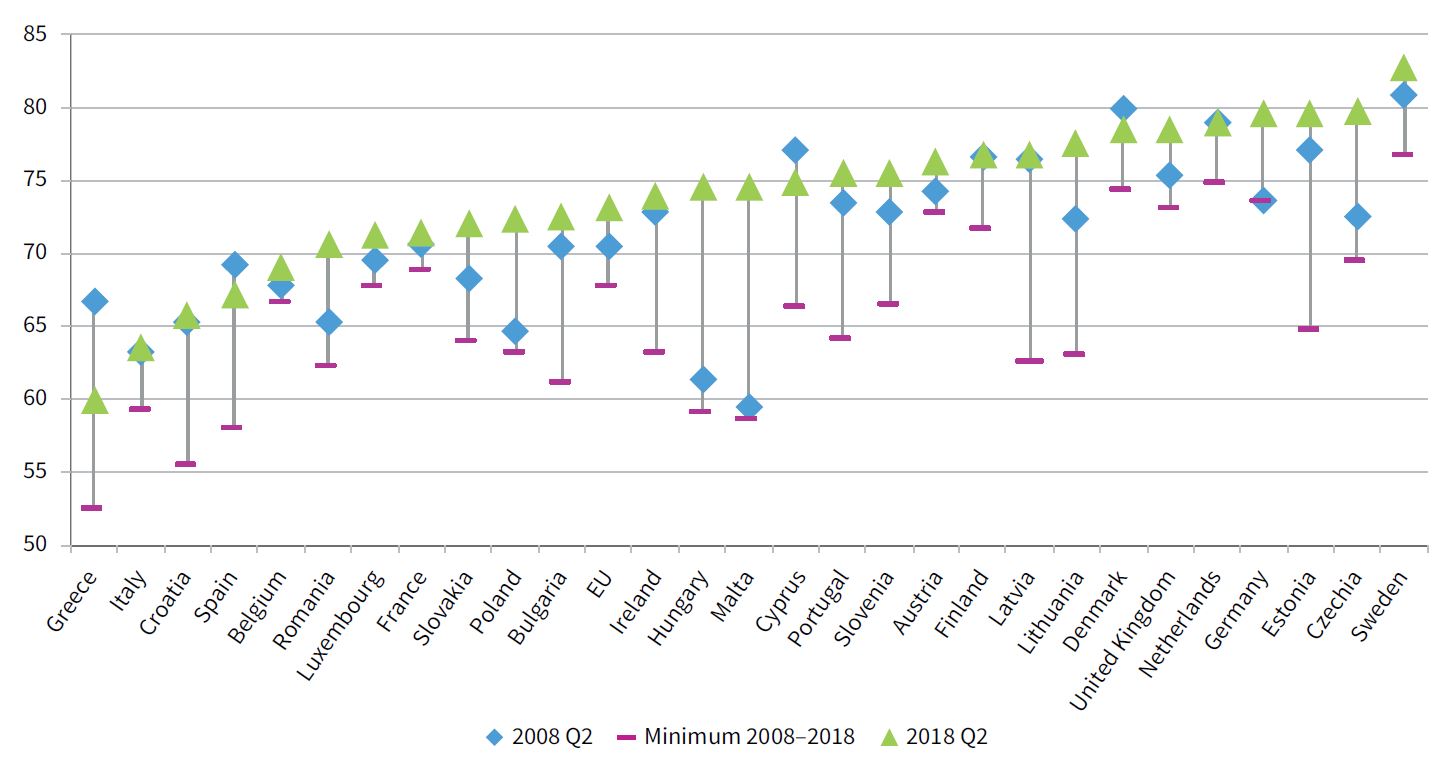

This focus is clearly borne out in the area of employment, where trends have been positive throughout 2015-2018. Employment reached an all-time high in the EU in 2018, rising to 73.2% of people aged 20–64 in the second quarter. Thirteen Member States passed the Europe 2020 target of a 75% employment rate, while another four (Ireland, Hungary, Malta and Cyprus) were within one percentage point of doing so. These high employment rates reflect not only economic growth, but also longer-term trends of increased participation in the labour market by women and older workers.

Unemployment continues to fall, dropping to 6.6% in December 2018, the lowest rate recorded in the EU since Eurostat started its monthly unemployment series in January 2000. It should be noted, however, that it remains high in some Member States, particularly Mediterranean countries such as Greece (18.6% in October 2018), Spain (14.3%) and Italy (10.3%). Long-term unemployment is falling, although at a slower rate, as is the youth unemployment rate (14.9% in December 2018) despite remaining very high in southern Europe.

Employment rates, EU Member States, Q2 2008–Q2 2018

Note: Rates for workers aged 20–64 years. Source: EU-LFS

Although we frequently use ‘pre-crisis levels’ as a benchmark for performance, we should not assume that we are re-establishing a pre-crisis labour market. The landscape has changed, most employment growth is now in high-paying, high-skilled jobs. This is, to a large extent, a result of the expansion of service sectors that tend to be predominantly high-skilled in terms of the qualifications and occupational profiles of employees, and the contraction of sectors that are predominantly low or middle-skilled.

There is undoubtedly more to do, reductions in the gender employment gap, which declined consistently over two decades, has stagnated at around 11.5% since 2015. Recent initiatives on work-life balance go in the right direction, but need to be further complemented if we want a fairer distribution of care responsibilities and more equal representation of women in the labour market. Economic inactivity is an issue that effects both men and women, and, despite overall declining inactivity rates, more than one in four working-age adults in the EU remain economically inactive.

A return to convergence

Unemployment has been the main factor determining income inequality and social exclusion. Having a job remains the best route to a decent standard of living, but these two things do not always go hand in hand, and concerns about the kind of work on offer have persisted throughout the recovery. Growth of part-time work, in many cases involuntary, continued in the first years of the recovery, starting to only slightly decline in very recent times. Growth in new forms of employment, such as work associated with online platforms, continued to contribute to more fragmented employment relations, raising further concerns; and back in 2013 there were indications that economic growth and falling unemployment were not being felt where it mattered most – in people’s pockets. However, there has since been an upturn, with average real wages increasing in more than two-thirds of EU countries.

Alongside the growth in wages, there has been a fall in wage inequality in most of the EU. Generally, wage inequality has declined in countries where wages increased most for the lowest-paid, as in the case of Germany, where there was the largest reduction in wage inequality among all EU countries in 2015, linked to the introduction of a minimum wage. In the broader spectrum of household income, falling incomes in several Member States during the Great Recession stalled convergence, but it has resumed more recently, mainly as a result of faster income growth in eastern European Member States.

Insecurity persists

More jobs, more money, what’s the problem? Although Europe is growing more prosperous, the aftertaste of the crisis lingers, particularly for those in southern Member States where the recovery is for some a relatively new phenomenon, and for others has not been fully translated into employment. But more generally, the levels of insecurity in Europe’s population around different risks persist, and even people who were not significantly affected in the bad years are not entirely confident that they won’t suffer in the years to come.

Just over 1 in 10 workers feel completely secure in their employment, confident that they won’t lose their job, and if they did, they would easily find a new one. That means that the vast majority of workers have some level of insecurity around their employment. Even among workers on permanent contracts, who have the highest levels of employment security, almost a quarter do not rule out losing their job in the next six months.

There is also insecurity around the affordability of healthcare: 17% of the EU population would find it difficult to pay for primary care, the most basic healthcare provision, at short notice, while 29% would find hospital care hard to cover. In some countries, these responses come not only from people in low-income groups, but also many people in middle-income groups and people who appear not to have had any problems previously covering healthcare costs.

Europeans are also unsure that they will have enough income to live on in old age, underlining the widely held doubts people have over the size of their pensions, both public and private, when the time comes to draw them down. Over half the EU population (56%) worry that their income in old age will not be adequate, while 13% are extremely worried; levels in Portugal, Spain and Greece are especially high. Insecurity is also reflected in the lower confidence people express about the future for coming generations, compared to their own.

The integration of migrants also remains an issue of tension and concern for many. Eurofound's 2016 European Quality of Life Survey showed that 40% respondents perceive a high level of tension between racial and ethnic groups, and 37% report high tension between religious groups. This perception is more prevalent in western European Member States that experienced high levels of immigration in recent years. Efforts at integration have been met with increasing resistance in a number of Member States, and arguments emphasising the potential of migrants to boost the dwindling labour supply in an ageing continent have been largely drowned out by concerns over the provision of public resources, and potential threats to national security.

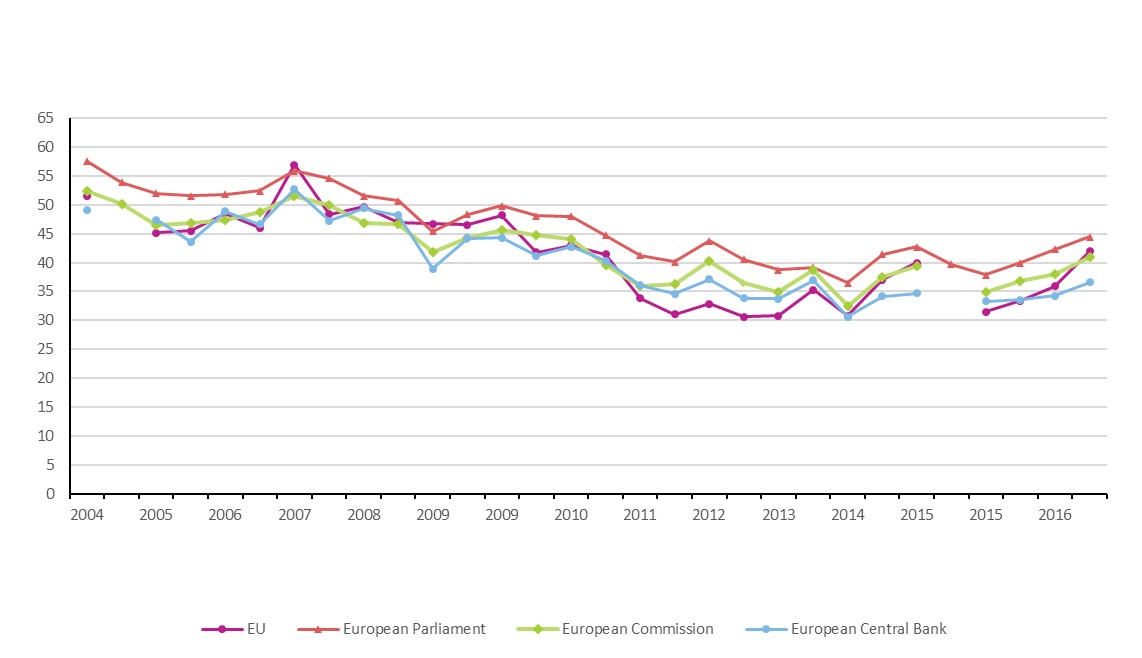

Percentage of people expressing trust in EU institutions, 2004–2017

Note: Gaps in the data are due to the omission of the question in some survey rounds. Source: Eurobarometer

A long-term rebuild

There can be little doubt that Europe is moving in the right direction both in terms of growth and jobs, and the recovery of the process of upward convergence. But remaining difficulties for some, and persisting malaise for many, make it no surprise that the restoration of faith in the European project has been sluggish. The underlying insecurities of the crisis has made people in Europe vulnerable to the negative rhetoric around the refugee crisis and immigration, which ignored the invaluable contribution of migrants to an ageing continent.

Europe’s economic rebound since 2013 has solved many issues, but it has not addressed all the challenges. The next political phase will need to focus on the implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights, which will seek to address some insecurities by delivering better quality of life and work for all citizens. Europe will continue to face challenges derived from structural change and its impact on labour markets; the necessary implementation of the Paris agreement on climate change; demographic tensions where ageing and migration will continue to be key factors, and growing geo-political unrest. The new Parliament and Commission will count on a period of grace, in terms of the economic context, that was not afforded to their predecessors. Eurofound, for its part, will continue to contribute with research that cuts through the rhetoric and focuses on the facts and figures.

Publication: Living and working in Europe 2015-2018

Author

Related content

20 May 2019

Living and working in Europe 2015-2018

Living and working in Europe 2015–2018 brings together Eurofound’s work on the quality of life, work and employment of EU citizens over the last four years of the outgoing European Parliament and Commission. It has a been a period of economic expansion, growing employment and rising living standards. There have been challenges, such as the growth of populism and the migration crisis, as well as opportunity, such as that offered by digitalisation. Over this period, Eurofound has answered some key questions about the living standards, well-being and working conditions of Europeans, highlighting where policymaking needs to target its efforts if it is to be seen to deliver. This yearbook summarises the main themes where the Agency provided answers. It is arranged into two sections: the first addresses living conditions, while the second looks at employment and working conditions. The theme of convergence cross-cuts the chapters and key areas are selected to see whether Member States are making progress and disparities between them decreasing. The yearbook is accompanied by the Consolidated annual activity report of the Authorising Officer for 2018, which is the Agency’s formal reporting on operations, staff and budgets – see Related content.

23 January 2018

European Quality of Life Survey 2016

Nearly 37,000 people in 33 European countries (28 EU Member States and 5 candidate countries) were interviewed in the last quarter of 2016 for the fourth wave of the European Quality of Life Survey. This overview report presents the findings for the EU Member States. It uses information from previous survey rounds, as well as other research, to look at trends in quality of life against a background of the changing social and economic profile of European societies. Ten years after the global economic crisis, it examines well-being and quality of life broadly, to include quality of society and public services. The findings indicate that differences between countries on many aspects are still prevalent – but with more nuanced narratives. Each Member State exhibits certain strengths in particular aspects of well-being, but multiple disadvantages are still more pronounced in some societies than in others; and in all countries significant social inequalities persist.

31 October 2017

Reactivate: Employment opportunities for economically inactive people

Employment policies tend to focus on unemployed people, but evidence indicates that many people who are economically inactive also have labour market potential. This report examines groups within the inactive population that find it difficult to enter or re-enter the labour market and explores the reasons why. It maps the characteristics and living conditions of these groups, discusses their willingness to work and examines the barriers that prevent them from doing so. The report also looks at strategies being implemented by Member States to promote the inclusion of those outside the labour market. It highlights that many inactive people would like to work in some capacity, particularly students and homemakers. Stressing the importance of focusing on the specific needs of the inactive population in designing and implementing effective strategies for their labour market integration, the report argues that Member States should fully implement the 2008 European Commission Recommendation on the active inclusion of people excluded from the labour market.

17 November 2016