Can short-time working save jobs during the COVID-19 crisis?

On 2 April, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced a new fund of up to €100 billion to support EU Member States to introduce short-time working or similar schemes, including for the self-employed, in an effort to safeguard jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Known as SURE (Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency), the initiative will finance loans on favourable terms to EU countries facing a ‘sudden and severe’ rise in spending on such schemes and is designed to show EU solidarity with hard hit Member States and workers.

On 2 April, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced a new fund of up to €100 billion to support EU Member States to introduce short-time working or similar schemes, including for the self-employed, in an effort to safeguard jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Known as SURE (Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency), the initiative will finance loans on favourable terms to EU countries facing a ‘sudden and severe’ rise in spending on such schemes and is designed to show EU solidarity with hard hit Member States and workers. While EU support for short-time working schemes is something new, the use of such schemes to cushion the impact of economic crisis is not; similar approaches were used by many Member States during the Great Recession.

Two types of job-protection measures

Close to 5 million jobs were lost between 2008 and 2010 alone, but these figures could have been higher if governments had not introduced various measures to support employment retention. These can basically be categorised into two types.

Short-time working schemes, where working time is reduced, but the employees are still working on an ongoing basis in the company; this helps to stabilise employment and support workers’ incomes.

Temporary lay-offs, where workers do not work at all for a period, but their employment contract is maintained, and they receive a certain level of income.

A common feature of both types of schemes is that workers are paid for more labour than they supply. The costs are shared between the employer and the state. For example, under the German Kurzarbeit scheme, short-time working compensation is paid by the employer, who is then reimbursed by the state at a flat rate of 60% of the worker’s salary (or 67% for workers with children). It is subject to a ceiling, meaning that actual salary reductions are greater for workers on higher incomes. However, a common feature of the German system of collective bargaining is that such replacement rates can be increased at sectoral or company level by collective agreements.

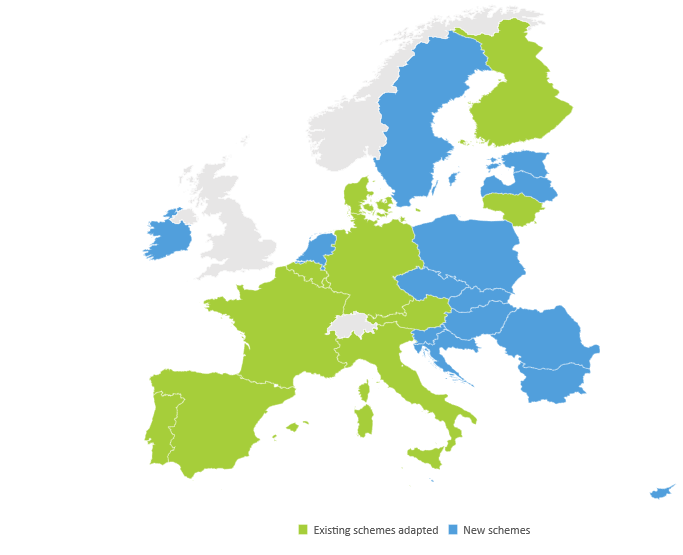

A brief overview of the impact of short-term working schemes during the Great Recession is presented in Eurofound’s recently published report Labour market change – Trends and policy approaches towards flexibilisation. This concludes that such schemes had a positive impact on employment. One assessment of the Kurzarbeit scheme found that it preserved around 580,000 jobs. [1] The speed with which countries have adapted their schemes to respond to the current crisis or have introduced new schemes, and the fact that the social partners in a number of companies have negotiated agreements on their use, shows that some lessons have been learned from the Great Recession. The chart below distinguishes between the Member States that adapted existing short-time working schemes for the COVID-19 crisis and those that introduced new schemes.

Figure: Member States shaded according to whether short-time working schemes are adapted or new

Given the impact of the containment provisions applied in most countries on the ability of so many businesses and services to continue operating – and the broad global economic implications of the pandemic – more employers are likely to resort to temporary lay-offs than during the previous crisis. Any EU-level guarantees, therefore, must cover these provisions too.

Need for additional supports

The types of supports provided across the EU differ in a number of ways, including eligibility criteria, length of time the support is available, income replacement rate and source of funding, among others. The experience of the Great Recession demonstrates the importance of social partner involvement and collective agreements negotiated at different levels to implement and shape the schemes. These are all the more important given that public wage guarantees can be significantly below the income workers had previously received. As a result, even if some form of short-time working scheme is available, it may not avert significant hardship for many families, which makes supplementary supports, such as mortgage payment holidays, vital.

It is also clear that workers on precarious contracts, such as fixed-term workers whose employment relationship terminates during the pandemic, are unlikely to benefit from short-time working or temporary lay-off schemes once their contracts end, so further efforts are required to support them. The same applies to the self-employed, although in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, many Member States have brought in specific measures to assist them (and these are also covered by the SURE scheme). The situation is also critical for casual workers and indeed undeclared workers, whose situations are even more precarious.

Filling the gap with training

An important feature of several support schemes implemented during the economic crisis was an attempt to enhance the skills of the workforce by offering training during the enforced downtime. However, the experience of these years also shows that such entirely sensible upskilling efforts were often thwarted for a number of reasons, including the unpredictability of the length of the downtime, the lack of flexibility and access to suitable training provision, and the challenge of drawing up meaningful training plans at short notice.

Not only are such challenges echoed during the current crisis but are arguably amplified by restrictions on the movement of people. The increased offer of online learning, however, could enable this form of training to come into its own. In this regard, technological progress over the last 10 years presents a favourable development as more digital learning content is now potentially available. Concerted efforts on the part of the social partners, management and workers are needed to ensure some positives can arise from the current crisis and that individuals can emerge from this situation better able to face the challenges of the post-COVID-19 labour market. In particular, training should consider new skills requirements such as those arising from the European Green Deal.

Image © Zivica Kerkez/Shutterstock

Map software © DSAT Editor, GeoNames

Reference

^ Hijzen, A. and Martin, S. (2013), ‘The role of short-time work schemes during the global financial crisis and early recovery: A cross-country analysis’, IZA Journal of Labor Policy, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 1–31.

Author

Tina Weber

Senior research managerTina Weber is a senior research manager in Eurofound’s Working Life unit. Her work has focused on labour shortages, the impact of hybrid work and an ‘always on’ culture and the right to disconnect, working conditions and social protection measures for self-employed workers and the impact of the twin transitions on employment, working conditions and industrial relations. She is responsible for studies assessing the representativeness of European social partner organisations. She has also carried out research on European Works Councils and the evolution of industrial relations and social dialogue in the European Union. Prior to joining Eurofound in 2019, she worked for a private research institute primarily carrying out impact assessments and evaluations of EU labour law and labour market policies. Tina holds a PhD in Political Sciences from the University of Edinburgh which focussed on the role of national trade unions and employers’ organisations in the European social dialogue.

Related content

16 April 2020

What have been the major trends and policy developments regarding the flexibilisation of employment in recent years? Eurofound’s work programme for 2017–2020 set out to document and capture these changes in the world of work. This flagship publication provides an overview of developments in Europe in the wake of the global financial crisis, as well as mapping the ongoing challenges and policy approaches taken at EU and national levels to find the right balance between flexibility and security in the labour market. Based, in part, on European Working Conditions Survey data, the findings of this report map labour market changes between 2008 and 2018 with a specific focus on working time, contract type and employment status.

23 November 2010

In the face of recession, falling demand and the consequent slowing of production, short-time working and temporary layoff schemes have been extended (or introduced) in many Member States. These schemes, often with the aid of public funds, reduce working time, while protecting workers’ incomes and company solvency; frequently, the time spent not working is used for training instead. This report examines the practice of reduced working time across Europe, and looks in detail at how it is implemented in 10 Member States, with a view to determining the contribution that such schemes can make in implementing the common principles of flexicurity, especially in light of the broad-based consensus they enjoy among the social partners. An executive summary is available.