How to ensure adequate minimum wages in an age of inflation

Minimum wages have risen significantly in 2022, as the EU Member States leave behind the cautious mood of the pandemic. However, rising inflation is eating up these wage increases, and only flexibility in the regular minimum wage setting processes may avoid generalised losses in purchasing power among minimum wage earners. On 6 June 2022, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament reached a political agreement on the Directive on adequate minimum wages proposed by the Commission in October 2020. Once formally approved, EU Member States will have to transpose it into national law within two years.

On 6 June 2022, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament reached a political agreement on the Directive on adequate minimum wages proposed by the Commission in October 2020. Once formally approved, EU Member States will have to transpose it into national law within two years.

The Directive intends to encourage the setting of wage floors at adequate levels in those countries that have statutory minimum wage systems (21 of the 27 Member States). Each Member State will decide on this adequate level and assess whether the minimum wage can guarantee a decent standard of living, taking into account the socioeconomic conditions, long-term productivity developments and the purchasing power of the minimum wage.

The minimum wage picture for 2022 across the EU provides an interesting illustration of how difficult this task can be. It highlights the challenges faced by policymakers when setting statutory rates (and also for the social partners when negotiating increases) in a context of inflation, which is eroding purchasing power.

Inflation eats up increases in nominal rates

Leaving behind the rather cautious increases of the 2021 exercise (between January 2020 and January 2021), with the pandemic compelling restraint, all Member States (except for Latvia) increased their statutory rates between January 2021 and January 2022, and to a greater extent than in the previous year in most countries. The median nominal increase across the Member States was 5% (the average increase being above 6%) and, as in 2021, the increases are much larger in central and eastern Europe.

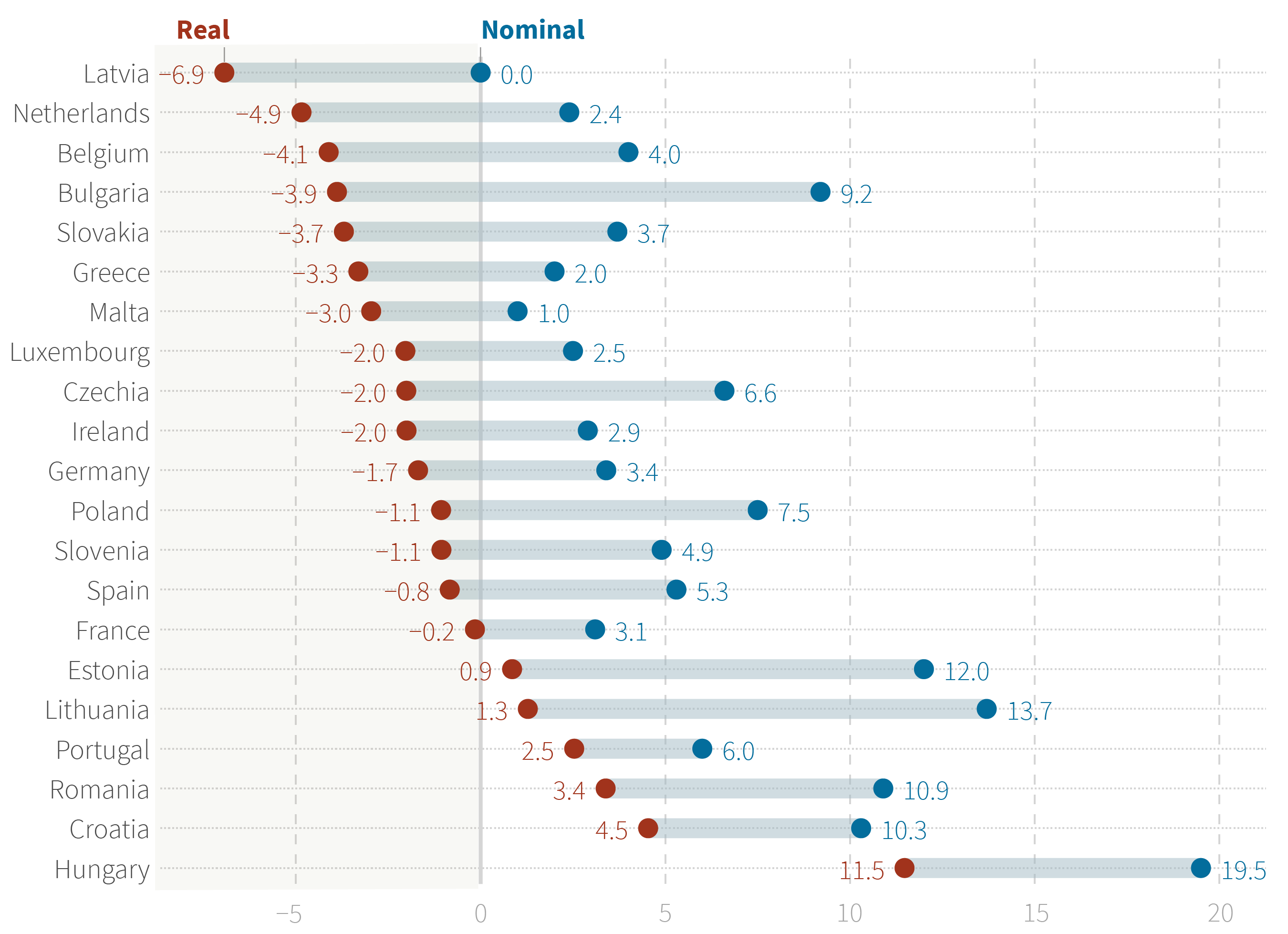

Nevertheless, these increases in nominal statutory rates have not generally boosted purchasing power among minimum wage earners due to rising inflation, which has taken centre stage after an absence of many years in Europe. As a result, statutory minimum wages in real terms declined in more than two-thirds of EU countries between January 2021 and January 2022. This means higher statutory rates are having a real-life impact in a less than a third of Member States – the six countries at the bottom of the figure below (several central and eastern European countries and Portugal).

Moreover, if present inflation trends continue, barely any country will escape the deterioration of the purchasing capacity of their minimum wage earners as the year progresses.

Figure: Year-on-year change (%) in statutory minimum wages, in real and nominal terms, January 2021–January 2022

Notes: Data for most Member States refer to the change between January 2021 and January 2022; for exceptions, see detailed notes in Minimum wages in 2022: Annual review. Member States are ranked in ascending order of the magnitude of the increase in statutory minimum wage rates in real terms.

Policy intervention could protect purchasing power

Action is needed. As it is unlikely that inflation will strongly subside this year, only a decided policy intervention – by wage setters or the negotiating parties – can ensure the living standards of minimum wage earners; this could be by means of additional increments to statutory rates, higher increases in negotiations, or other support measures for low-paid employees.

Only around half of Member States with statutory minimum wages are obliged by law to take inflation or changing living costs into account when setting rates. [1] This is an area where the EU’s Directive on adequate minimum wages could bring about significant changes. By requiring wage setters to use clear criteria such as the purchasing power of the minimum wage, the Directive will oblige them to take account of changes in the cost of living in order to maintain living standards among minimum wage workers. It remains to be seen, however, how quickly wage setters will react or be able to react when circumstances change.

Some Member States with automatic indexation mechanisms included in their minimum wage setting process – such as Belgium, France, and Luxembourg – have been quicker in uprating wages in line with inflation. For instance, two increases of 2% each were triggered in Belgium in March and May 2022 as a result of indexation, following two identical increases already implemented in September 2021 and January 2022.

The Directive will require those Member States without such automatic indexation mechanisms to update their statutory minimum wages at least every second year. Even though most have a yearly update cycle already in place (and a few regularly uprate also within the year), for someone who is already financially stretched, a wait of one to two years to see their purchasing power re-established can seem like an eternity.

This is one reason why it is important to maintain the possibility of ad hoc policy interventions in minimum wage setting processes, if such interventions are justified – as is the case in this context of high inflation. For instance, Greece decided to upgrade its statutory minimum wage by more than 7% from May 2022, outside the regular uprating cycle, due to inflation concerns.

How adequate the wages of minimum wage earners will be at the end of 2022 will depend on the flexibility of the established procedures for statutory minimum wage setting and the political will to maintain purchasing power of the lowest paid. It will also depend on the will of the social partners and their ability to arrive at negotiated outcomes that take inflationary pressures into account.

More details on minimum wage increases and wage setting processes have just been launched in the report Minimum wages in 2022: Annual review.

Image © focusandblur/Adobe Stock

Reference

^ Eurofound (2019), Minimum wages in 2019: Annual review, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Authors

Carlos Vacas‑Soriano

Senior research managerCarlos Vacas Soriano is a senior research manager in the Employment unit at Eurofound. He works on topics related to wage and income inequalities, minimum wages, low pay, job quality, temporary employment and segmentation, and job quality. Prior to joining Eurofound in 2010, he worked as a macroeconomic analyst for the European Commission and as a researcher in European labour markets at the Spanish Central Bank. He holds an MA in European Economic Studies from the College of Europe in Bruges and a PhD in Labour Economics from the University of Salamanca (Doctor Europaeus).

Christine Aumayr-Pintar

Senior research managerChristine Aumayr-Pintar is a senior research manager in the Working Life unit at Eurofound. She coordinates Eurofound’s research on social dialogue and industrial relations and oversees the Network of Eurofound Correspondents (NEC). Her primary research expertise – approached from a comparative EU-wide standpoint – centres on minimum wages, collectively negotiated pay and gender pay transparency. Prior to joining Eurofound in 2009 she was a labour markets and regional economics researcher at Joanneum Research in Austria. She earned a Master's degree in Economics and a PhD in Social Science/Economics having studied economics in Graz, Vienna and Jönköping.

Related content

15 June 2022

After a cautious round of minimum wage setting for 2021, nominal rates rose significantly for 2022 as the negative consequences of the pandemic eased and economies and labour markets improved. In this context, 20 of the 21 EU Member States with statutory minimum wages raised their rates. Substantial growth was apparent in the central and eastern European Member States compared with the pre-enlargement Member States, while the largest increase occurred in Germany. When inflation is taken into account, however, the minimum wage increased in real terms in only six Member States.

If present inflation trends continue, minimum wages will barely grow at all in real terms in any country in 2022. Significant losses in the purchasing capacity of minimum wage earners are likely to dominate the picture, unless the issue is addressed by policy changes during the year. The processes for minimum wage setting and related legislation in the EU have remained unchanged, by and large, or were adapted only slightly for 2022.

27 January 2022