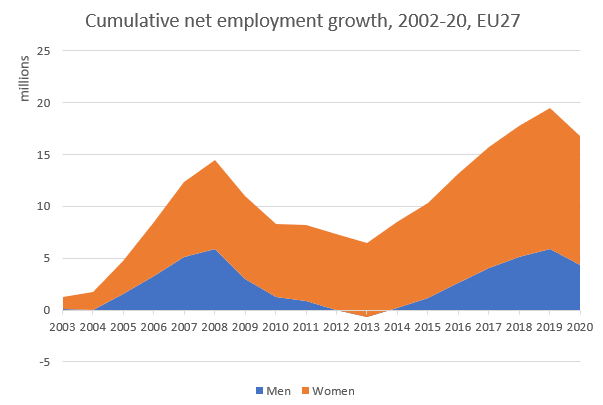

One of the most striking developments of the last half-century has been the huge rise in female labour market participation in advanced economies. More than two out of every three net new jobs created over the last two decades in the EU have been taken up by women, who now account for 46% of the workforce in the EU27. In 2002, the comparable figure was less than 43% and in the early 1990s it was less than 40%. This is a reflection of growing opportunities for women as well as the consolidation of a broader trend towards dual earner households.

Source: EU-LFS (author’s elaboration)

EU policy foresees further progress in this area. One of the subsidiary targets of the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan is a halving of the gender employment gap - currently standing at about 11% – over this decade. This will require a further three new female jobs for every one new male job up to 2030.

We can say then that the labour market has been – and is likely to continue – generating greater possibilities for women. But are social structures adapting to accommodate these positive changes? The answer to that question is mainly negative. The provision of good quality and affordable childcare is uneven across EU Member States and remains an impediment to a full and active labour market participation, especially for working mothers. Working women continue to shoulder a disproportionate share of unpaid work in terms of domestic tasks and caring for dependents.

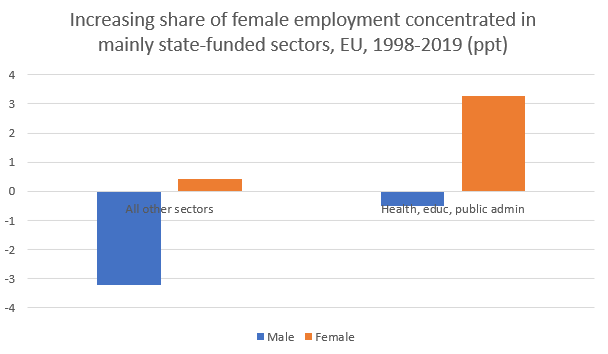

And care responsibilities are not only disproportionately borne by women at home, but also in the workplace and labour market more generally. One of the surprising patterns identified in a recent joint Eurofound-European Commission JRC report was that occupational segregation by gender had increased in the EU over the last two decades, notwithstanding the shrinking gender employment gap. The share of EU workers in gender-mixed jobs (those with at least 40% of male and female headcount) declined from 27 % in 1998 to 18 % in 2019.

Source: LFS (authors’ calculations) in Eurofound-European Commission JRC 2021.

Note: data covers EU25 (EU27 except Croatia and Malta).

Indeed, the large expansion of female employment over the last two decades has taken place primarily in jobs which already had a majority of female employment, notably ‘caring’ jobs in the predominantly state-paid sectors of health, education and social care.

The pandemic has brought some of these gender differences into sharper focus. Women were more likely to be working in many essential, front-line jobs with all of the attendant stresses. Meanwhile, job loss in the early, most severe phase of the crisis was highest amongst low-paid women, those working in hospitality sector jobs most affected by lockdowns and social distancing measures.

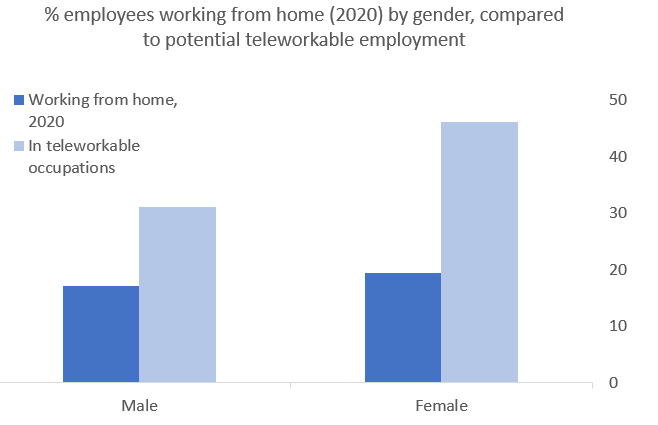

Women were also more likely than men to have shifted to working from home during the crisis or to have reduced their paid working hours, in part as a response to closures of schools and care facilities. Again, where flexibility at the household level was required to deal with unforeseen domestic responsibilities, it was primarily women who took up the slack.

Source: EU-LFS, Sostero et al (2020, pdf ) for teleworkable employment estimates.

For this reason, the prospect of an increased incidence of remote working post-crisis raises many questions from a gender equality perspective. Firstly, women are significantly more likely to be working in jobs that can be worked remotely (see above). Secondly, survey evidence on preferred working arrangements after the pandemic suggest that the increased availability of splitting work between the employer’s premises and home will mainly be taken up by women. This may further entrench gender divides in unpaid work if used as a strategy for combining paid with unpaid work. It will also mean that the risks associated with working from home evident in Eurofound research before and during the pandemic – longer hours, working during free time, isolation - are disproportionately borne by women. Thirdly, a scenario where workplace presence will be more male-dominated entails potentially negative consequences for visibility, career development and promotion for working women. Hybrid working could be a double-edged sword, another reminder that flexibility often comes at a cost for working women.

Reducing gender gaps in the labour market means more men deciding to become nurses or teachers or childcare workers. This may be as important as a fair sharing of domestic responsibilities in weakening persistent gender stereotypes. Gender parity in employment is conceivably on the horizon but narrowing deep-rooted gender gaps in both paid and unpaid work is one precondition for it to take place.

More information

- Webinar: #AskTheExpert: Reassessing gender inequalities in the labour market: impact of COVID-19 pandemic

- Eurofound Talks: Episode 4 - Gender equality

- Infographic: Gender equality

- Topic: Gender equality