Minimum wages: Trends and early impacts of the EU directive

Publicēts: 13 May 2025

National minimum wages have increased significantly across EU Member States over the past decades, with a strong upward convergence in central and eastern European countries. Minimum wage has become an increasingly popular policy instrument among governments, resulting in minimum wage floors rising faster than average and median wages. This trend has been reinforced by the EU directive on adequate minimum wages, which is already influencing minimum wage-setting practices in several Member States.

All EU Member States have minimum wage systems in place. However, this article focuses on the twenty-two Member States that currently have a single, universal wage floor in the form of a national minimum wage. It excludes the five Member States without one – Austria, Denmark, Italy, Finland and Sweden – where multiple wage floors in specific sectors and/or occupations are set through collective agreements by social partners.

Regional differences: Upward convergence among post-2004 Member States

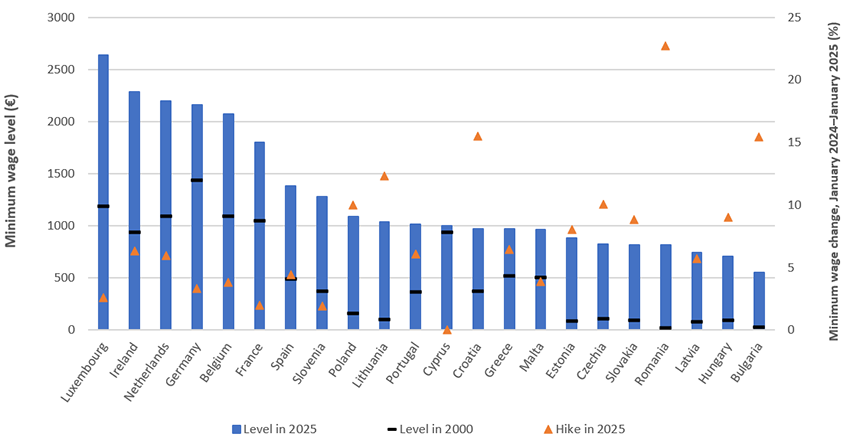

The gap in minimum wage levels (and wage levels) across the EU has narrowed considerably over the past decades, largely due to the strong growth among central and eastern European Member States (see Figure 1).

In 2000, the minimum wage level in Luxembourg was more than 47 times higher than in Romania. By 2025, the difference between the highest and lowest rates – Luxembourg and Bulgaria – has narrowed to just under five times. Twenty-five years ago, monthly minimum wage rates in many central and eastern European countries, including Romania, Bulgaria, Latvia, Estonia, Slovakia, were below €100. In others, such as Hungary, Lithuania and Czechia, they were only slightly above that threshold, with Poland reaching up to €161.

Since then, central and eastern European countries have accomplished a remarkable upward convergence, with minimum wage levels increasing significantly from their initial levels, narrowing disparities and even pushing nominal minimum wages in countries like Poland and Lithuania ahead of those in Portugal and Greece.

This genuine convergence goes beyond differences in cost of living. While cross-country variations in minimum wage levels are partially due to differences in price levels, these differences, and especially their notable compression over time, are also evident when minimum wages are expressed in purchasing power standards. In this case, the ratio between the highest and lowest minimum wage has declined from more than 20:1 in 2000 to 2:1 in 2025 – compared to 47:1 and almost 5:1, respectively, when measured in euros.

Despite strong convergence, significant differences exist

As of January 2025, monthly minimum wage rates range from nearly €2,638 in Luxembourg to just €551 in Bulgaria.

A clear regional picture emerges.

The highest rates are found in six western European countries – Luxembourg, Ireland, Netherlands, Germany, Belgium and France – where the lowest rate is €1,802. A middle group of nine countries includes both older Member States (that joined the EU before 2004) and newer ones from the Mediterranean region, with minimum wages ranging from around €1,381 in Spain to €960 or more in Croatia, Greece and Malta. The lowest group includes seven central and eastern European Member States that joined the EU after 2004, where rates range from €886 in Estonia to €551 in Bulgaria.

These differences in minimum wage levels, which largely mirror broader pay levels, are one of the main drivers of intra-EU labour mobility, particularly migration from eastern and southern Member States to higher-income western and northern Member States.

Figure 1: National minimum wage levels in January 2000 and 2025, and percentage changes between 2000 and 2025, EU Member States

Notes: Countries are ranked by their minimum wage level in January 2025. For the January 2000 data, alternate reference years are used where necessary (January 2001 for Ireland, January 2009 for Croatia, January 2023 for Cyprus, January 2015 for Germany). Growth rates between January 2024 and January 2025 are calculated in national currencies.

Source: Eurostat and Eurofound calculations

Minimum wage changes between January 2024 and January 2025

The same regional picture emerges, with increases generally larger in countries where minimum wage levels were relatively low. The nine highest nominal hikes were all recorded in central and eastern European Member States, ranging from nearly 23% in Romania to 8% in Estonia. In contrast, increases in the older EU Member States were generally more moderate.

Monthly minimum wage rates increased in all Member States except Cyprus. Although nominal increases were somewhat more moderate than in the previous year, the continued moderation of inflation meant that minimum wage earners experienced gains in purchasing power in most Member States.

The influence of the new Minimum Wage Directive

The rising popularity of minimum wages as a policy instrument across EU Member States has been reinforced by the new Minimum Wage Directive. The directive, which was to be transposed into national legislation by November 2024, aims – among other objectives – to ensure that Member States establish frameworks that make statutory minimum wages ‘adequate’.

Growing influence on statutory minimum wage setting

While national governments remain responsible for setting minimum wage rates, the directive reinforces the framework by requiring frequent updates, clear criteria for determining minimum wage levels and the involvement of consultative bodies and social partners.

It also requires Member States to choose ‘indicative reference values’ to guide their assessment of the adequacy of statutory minimum wages, with 60% of the gross median or 50% of the gross average wage mentioned as examples.

In recent years, particularly for 2025, a growing number of Member States are using these reference values when deciding on their minimum wage hikes. Most use the average wage rather than the median and in many cases apply the 50% threshold, or a value close to it. Even before the directive, minimum wages were increasing faster than average or median wages across most EU Member States, and this trend is likely to continue as most Member States have not yet reached their targeted relative levels.

As Member States approach these reference values, minimum wages are becoming fairer in relation to the wages of the working population at large, addressing one key dimension of adequacy under the directive. However, the second dimension – whether minimum wages ensure an adequate standard of living – remains less developed in practice. This dimension depends not only on the minimum wage level itself, but also on the cost of living and other factors shaping household income, such as household composition, wages of other family members and the tax and benefit systems. To date, EU Member States have taken very limited action in assessing this dimension of minimum wage adequacy. Slovenia is the only Member State that links minimum wage hikes to changes in a defined basket of goods and services. While Romania adopted a similar approach, it has not yet been implemented.

Transposition and future steps

Although the transposition deadline has passed, some Member States have yet to fully implement the directive. Where changes have been introduced, they have tended to be incremental rather than major overhauls of the minimum wage setting frameworks. In most cases, countries have simply included the directive’s minimum wage-setting elements by adding its exact wording directly into national legislation, alongside pre-existing criteria. Similarly, the role of the new consultative bodies has most often been assigned to existing (tripartite) wage setting institutions or commissions.

Even if these changes ‘on paper’ do not seem to be major, it will be interesting to monitor their practical implications over the coming years. For instance, once Member States meet the reference values, will future minimum wage increases become more moderate and aligned with average/median wages so that such relative thresholds are continuously met? Or will the reference thresholds themselves be increased?

A crucial pending issue is the upcoming ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union on the directive itself. The decision, expected in 2025, will address Denmark’s request for full or partial annulment of the directive. It could have significant implications for the EU framework and policy approach to minimum wages, particularly at a time when issues such as competitiveness are gaining prominence in the EU policy debate.

Image © jesson-mata/Unsplash

Eurofound iesaka šo publikāciju citēt šādi.

Eurofound (2025), Minimum wages: Trends and early impacts of the EU directive, article.